Hals bet everything on portraiture… It was a profession, not a calling. His job was to disappear into the paint.

(Zachary Fine)

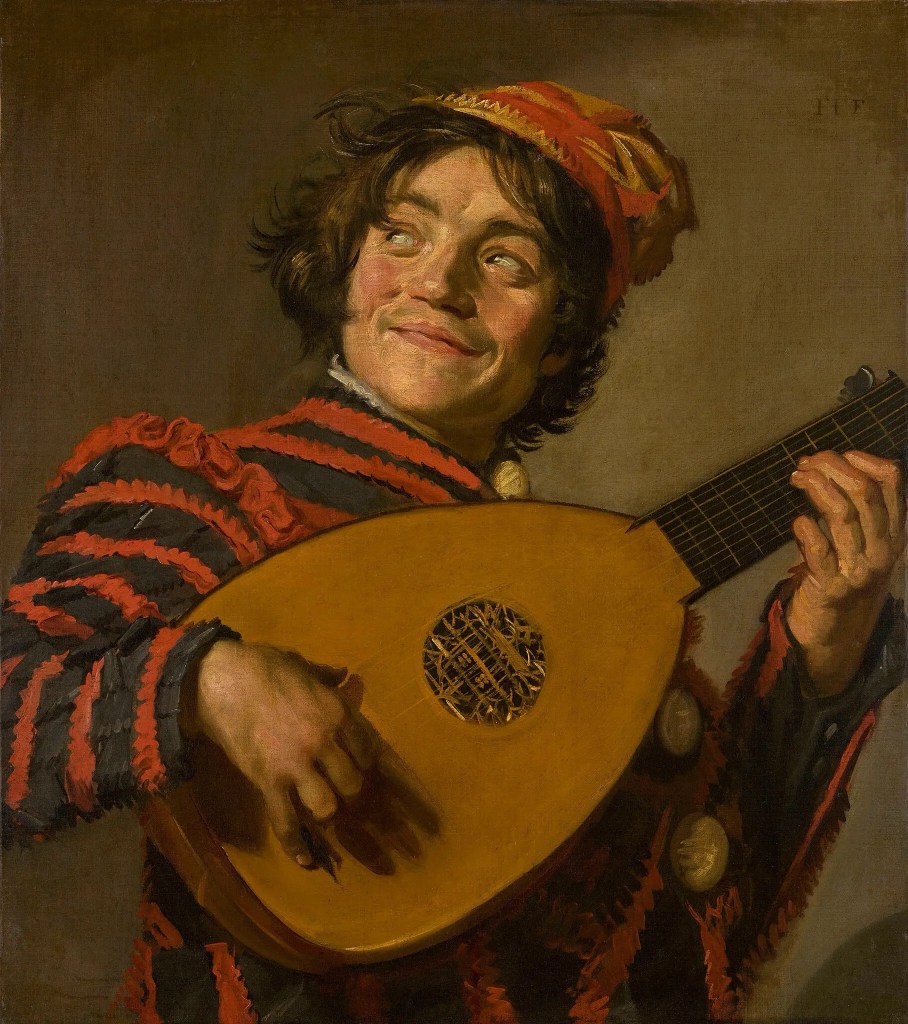

For me Vermeer is glassy and distant where Hals is rudely… reachable. The tossed-off affect of his paintings’ brushiness draws one in. (A museum guard allowed an awed Whistler to feel up a Hals canvas.) Hals’s intention, according to an expert, “was to make the paint itself visible.” (Shades of Van Gogh!)

The key to the sense of spontaneity was not speed, but loose brushwork — paint vigorously daubed onto the canvas with thick, expressive strokes (Nina Siegal)… Even when you’re standing ten feet back from the canvas, you can peel off individual brushstrokes with your eyes. They’re just floating there, like little spears of light. (Zachary Fine)

Hals bet the farm on portraiture, and my own bent for breaking lances on faces adds to my affinity with him. I, too, have had to confront (not with his success) mouth and teeth issues, including the grin-grimace ambiguity. In my humble experience it’s the eyes that must somehow break the tie.

At the time Hals was working, “No one really painted laughter and joy in paintings,” [said an expert]. “Most other artists shunned it, first because it was kind of against decorum, but also because it’s incredibly difficult.” By showing teeth, he explained, artists run the risk of making the subject appear to grimace, or even cry: It’s a delicate balance of brushwork to get a smile right. (Nina Siegal)

Hals’s paintings stir me in distinctive ways. The frippery encasing “The Laughing Cavalier” is carnivalesque. I want to knock the cocked hat off the corpulent, smirking dandy and addle his curvaceous moustache.

The “Regents of the Old Men’s Alms House” makes me laugh in a good way while savoring the fact that it was painted by a Methuselah for his time whose legend is to have wasted his life in the tavern. Zachary Fine’s description enhances the experience:

When we reach his last piece in the exhibition, “Regents of the Old Men’s Alms House” (1664), Hals has gone full Manet. He’s in his eighties and appears to be freed from whatever demands his sitters might have. One of the almshouse regents looks like a melted puppet. Another could be easily mistaken for a corpse.

This is where Fine’s quotation of Lucian Freud is apt: Hals was “fated to look modern.”

Sources

Nina Siegal, “Frans Hals and the Art of Laughter,” New York Times, 10-2-23.

Zachary Fine, “The Man Who Changed Portraiture,” newyorker.com, 11-3-2023.

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicaDative. All rights reserved

Enjoyed your thoughts on Frans Hals – evoking the same joyful fun as the paintings themselves.

I think I read somewhere there is going to be a major exhibition of his work in Holland in the not too distant future. Good post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Andy. I’ve found myself several times zooming the lute player and marveling at Hals’s deft treatment of the hands, the features. The face seems so *modern*, for lack of a better word! So “present.” I appreciate your feedback.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: ‘Heartfelt, Slapdash, But Unredeemed by Art’ | EthicalDative