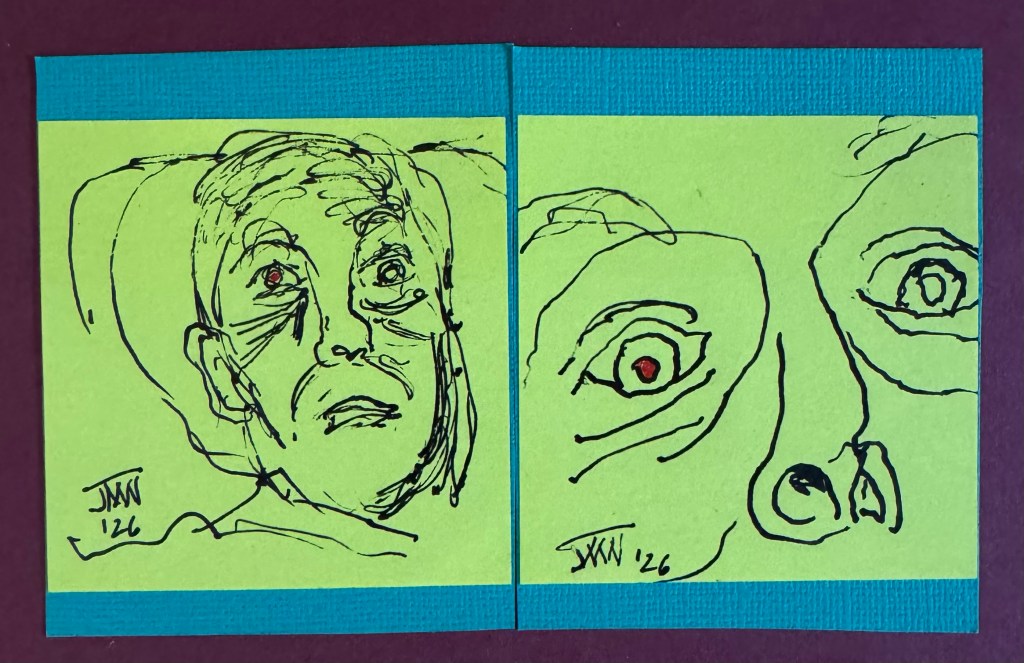

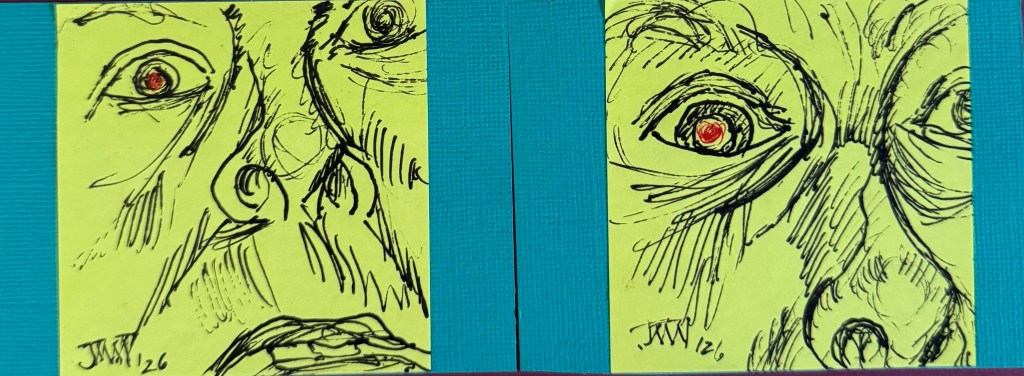

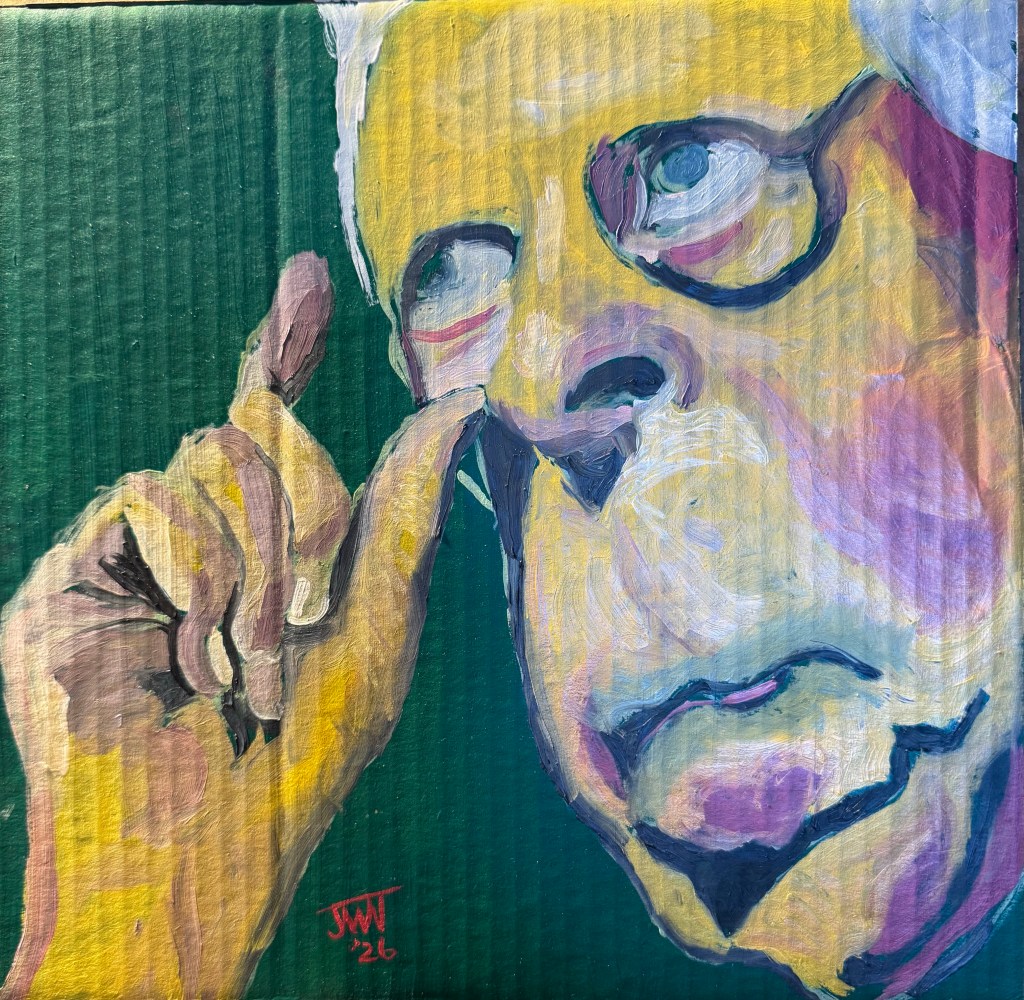

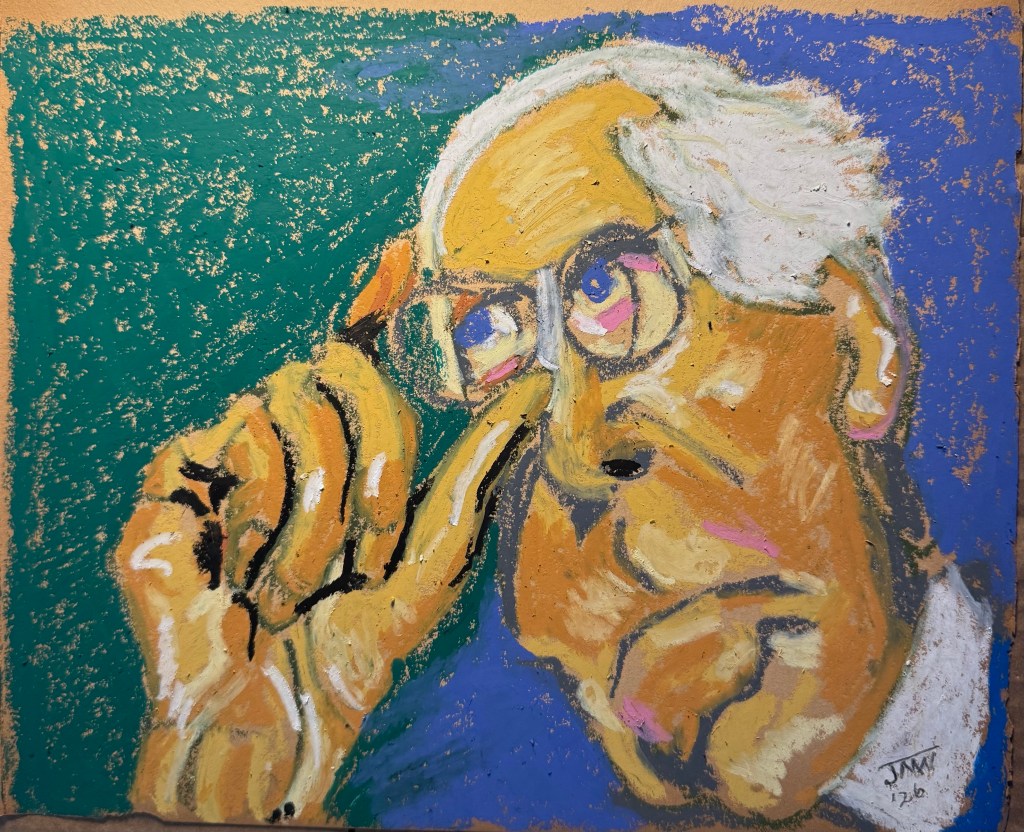

Bad Epstein moonrise 1.

By this time I should have acquired enough sense to realize that the cause of wars is sin.

(Thomas Merton, The Seven-Storey Mountain)

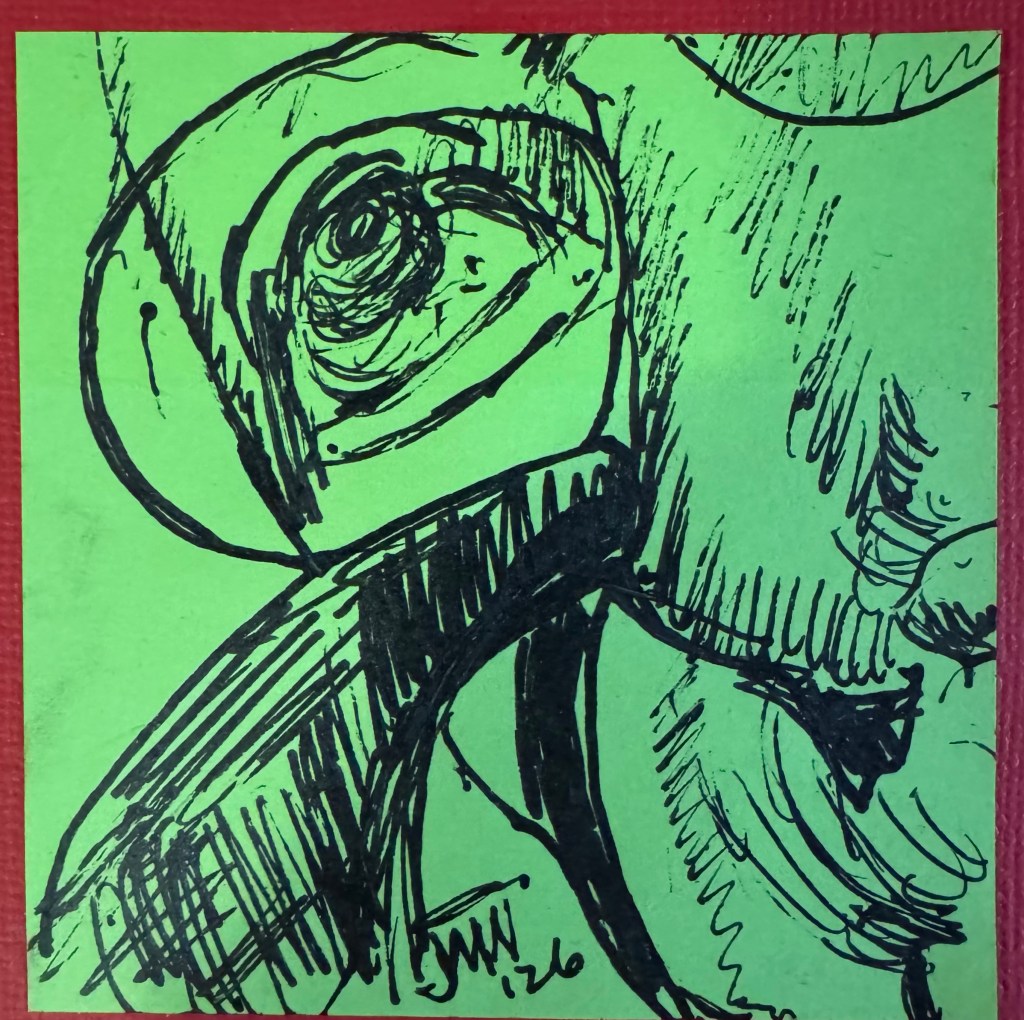

GREENLAND FROTTAGE

The sub-scalpal domain north of the eyeballs

Is given to a chronic restivenessness

Sharp as a rhinoceros’s horn.

It knows that there be monsters to undress.

Confusion says, “Between extremes is me.

I spy with my middle eye mud bricks,

Immiserating, demoniacal

Perversion angels townhoused on the Styx.”

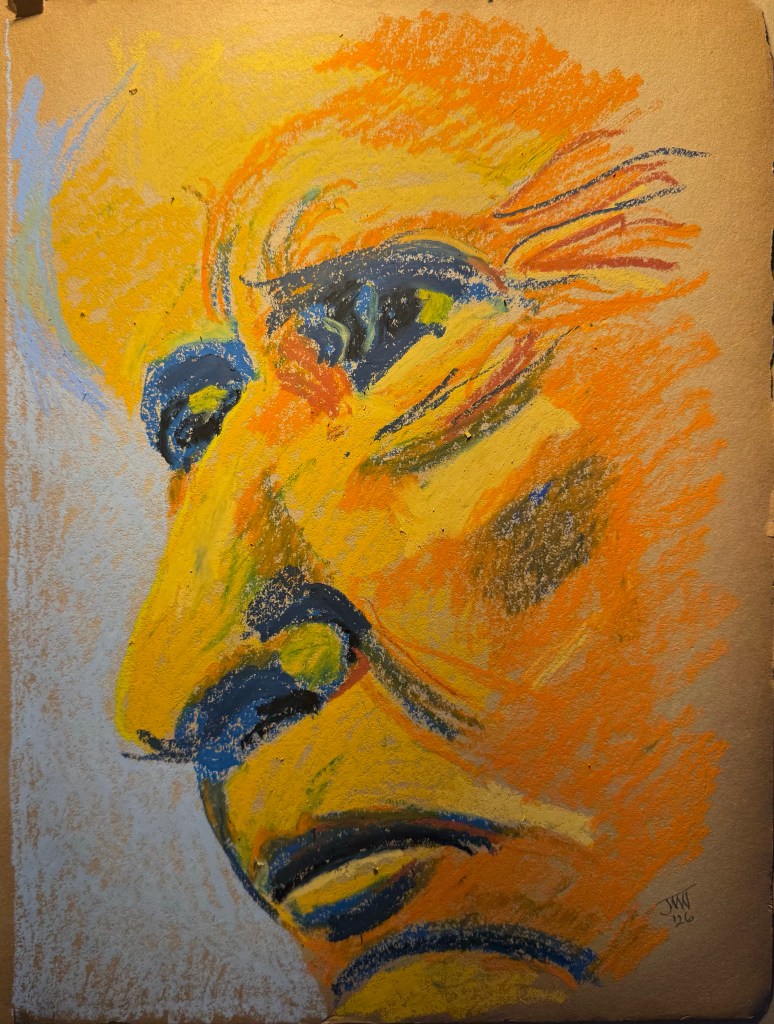

Bad Epstein moonrise 2.

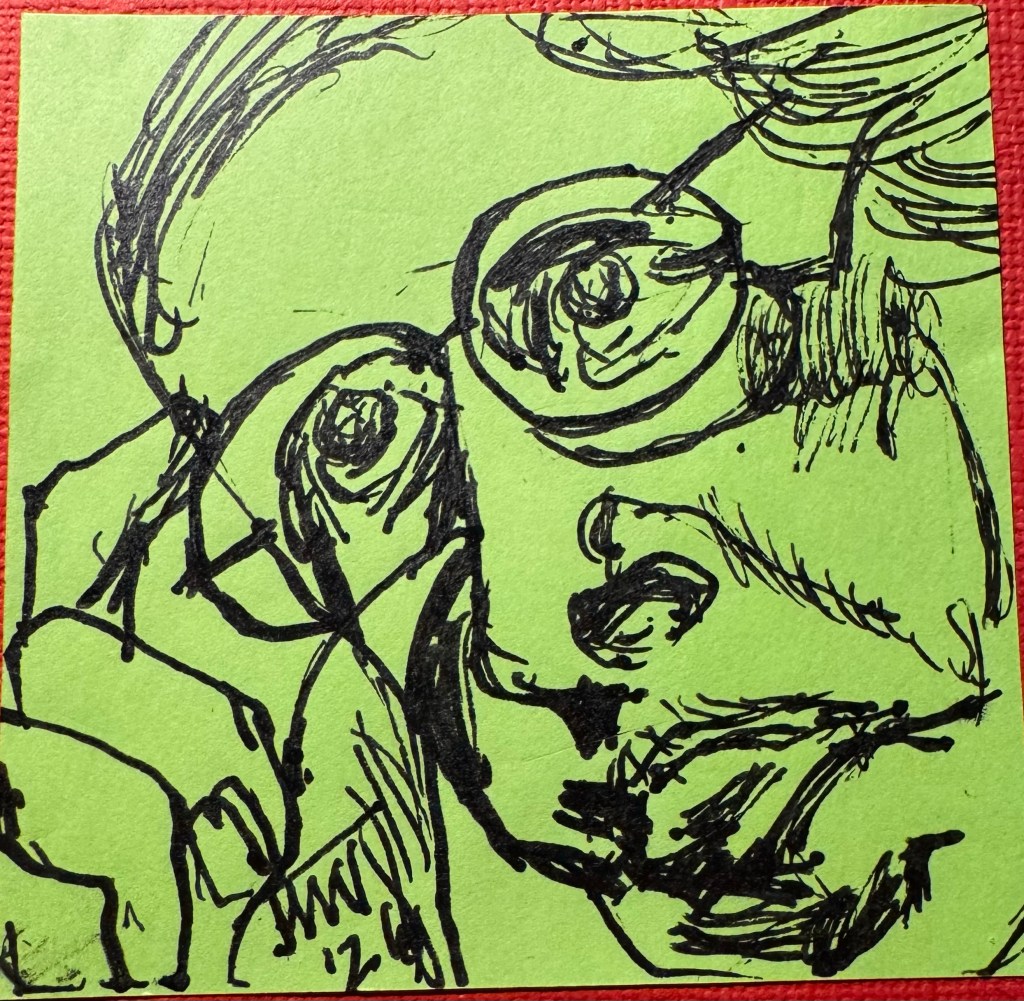

PERSIAN SHAH-NA-NA

Drunk on gospels, creeds and pentateuchs,

The beast with five backs televises havoc,

Absent without leave the prince of peace.

Stunned by gospels, creeds and pentateuchs,

The world at large sips bitter gall and pukes

As private banquets romp on the Potomac.

Bought with gospels, creeds and pentateuchs,

The beast with five backs, suckered, runs amok.

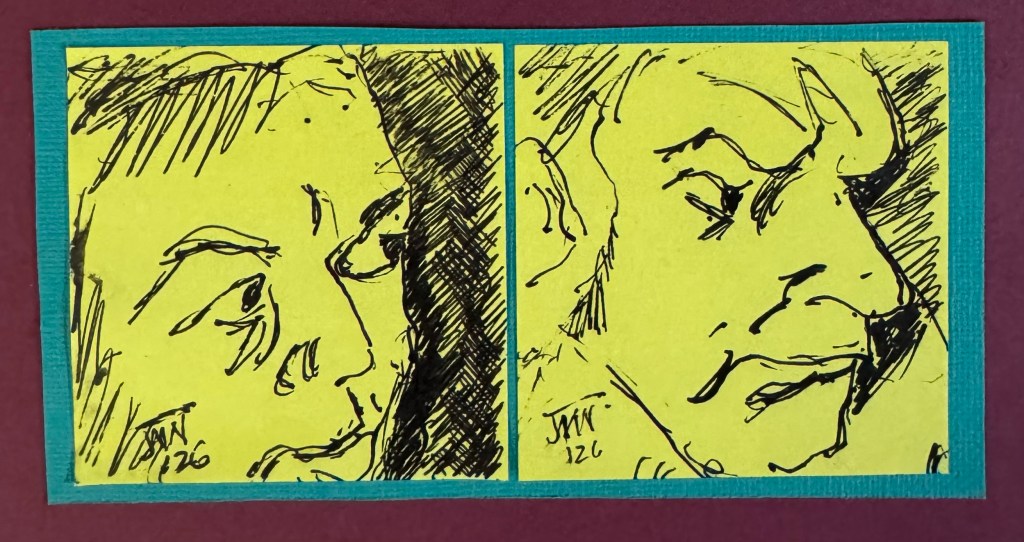

Couple of standup Brit cops in a functioning justice system doing their job without fear or favor.

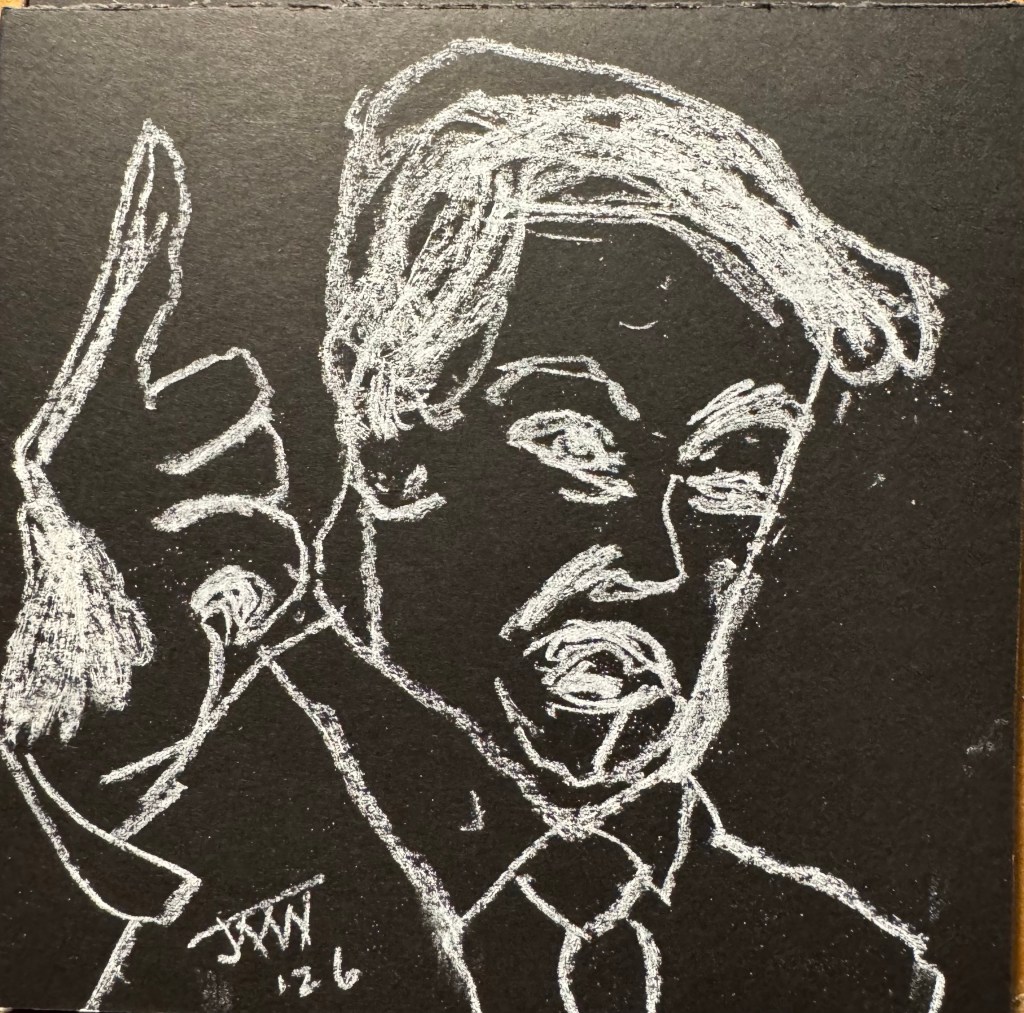

There’s more distraction here if needed.

(c) 2026 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Glimpses and Manias (I’m So All About This Painting)

Lee Krasner’s grid-like “Composition” (1949), featuring hieroglyphic-like forms, will be featured in the exhibition “Krasner and Pollock: Past Continuous,” opening Oct. 4 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. With its visual complexity it opened new avenues for explorations in abstraction. Credit… Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [New York Times caption and illustration]

This thumping doodle by Lee Krasner — whatever it is, I like it, not least because it looks like some kind of writing devised by a sensibility going for broke. For that matter it could be the shower tile of a Venusian. The “Jewish girl from Brooklyn’s” early influences are pegged as “Hebrew calligraphy, cubism, Mondrian and especially Matisse.”

Krasner’s artefact conveys well nigh infinite possibility as to what a painting can be or what could be a painting. Nothing adjacent to “pretty” or “ugly,” just intricacy tantamount to a perfervid tramontane hallucination. It makes her partner’s drips look lazy.

The tale of Krasner’s 1950s collages is one of those creation stories that love to tell themselves and be told. They acquire the status of deep lore surrounding deceased practitioners whose leavings accrete value trousered by museums and galleries.

At a dead end after struggling with some recalcitrant drawings, she ripped them in half and threw them on the floor. “Having finished this bout of destruction, I slammed the door and walked away,” she said. Days later, she saw the possibilities. She tore more, she pasted those scraps to paper — and later Masonite — and interlaced them with tangled, cursive, or thrusting marks.

Who hasn’t struggled with a “recalcitrant” drawing? The upshot in this case has the heat of annunciation: “Lo,” spake the angel, a connoisseur. “My jaw dropped. She was a really great painter.”

(Amei Wallach, “For Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, Equal Footing at the Met,” New York Times, 2-25-26)

(c) 2026 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved