The tiny speaker in Megan Denton’s “A Girl and Her Fireplace” (Poetry, December 2024) is off to a shaky start.

Born on a new moon, one minute after my sister

and one pound less, my ribcage was full

of roosting songbirds and hers a steady drum,

and when all three pounds of me came earthside I heard God say,

everyone you love lives here. […]

I was let loose in a world too cruel for me, […]

Wee unchurched mountain girl,

planting jelly beans in the forest […]

At thirty-four and many years sick, sometimes I still think

of all the people throwing coins into fountains. […]

What the superficially puny being possessed of indomitable spunk is grateful for is solitude and self-reliance:

[…] I thank

every tipped domino that led me here: my first winter

completely alone, save for the glowworm orange

of my hearth. […]

She confesses her terror, and admits to sitting a little too close to the sustaining warmth.

[…] Forgive me. I am at the doorway

of the firebox, feeding all my prayers to the flame.

Coins into fountains, prayers into flame: I read the two images as related, expressing a longing for prolonged joy fiercely voiced from within a heightened awareness of contingency. Denton’s second poem, “Ars Poetica with Invocation,” meshes tightly with “A Girl and Her Fireplace.” Here’s how it starts:

Which way to the monster cage? I am in my god body now—

in my sandy foxhole

sat backwards in a chair.

The speaker says she had “wintered in a lighthouse not far from here” (callback to that firebox above). Her imagination is her monastery:

[…] My little monk feet

clack about my mugwort garden: […]

Push against me as hard as you can. Still I will

go on swinging my war ax,

despite my stringbean heart. All the queen’s horses

and all the queen’s men could not stop

the scritch of my pen.

Next to the steel resolve of that stringbean heart, set down in lapidary words, autocracies don’t stand a chance. No wonder they crucify their poets. After the musky putins have ridden their cock-rockets off to Banbury Cross or wherever (and God speed), those with the mountain girl’s mettle will be around to model enduring valor. Remember how Samau’al burns the woman from a hostile tribe who sneers at the tiny number of his cohort on the battlefield:

tu^ayyir(u)-nā ‘an-nā qalīl(un) ^adīd(u)-nā | fa-qult(u) la-hā ‘inna-l-kirām(a) qalīl(u)*

She shrieks disdain at us for being so few in number. I said to her, “So true, madame. The noble are not plentiful.”

Note

*As-Samau’al’s poem is from the 6th century A.D. The Arabic text I’ve transliterated is from A.J. Arberry, Arabic Poetry: A Primer for Students, Cambridge University Press, 1965. The translation is mine.

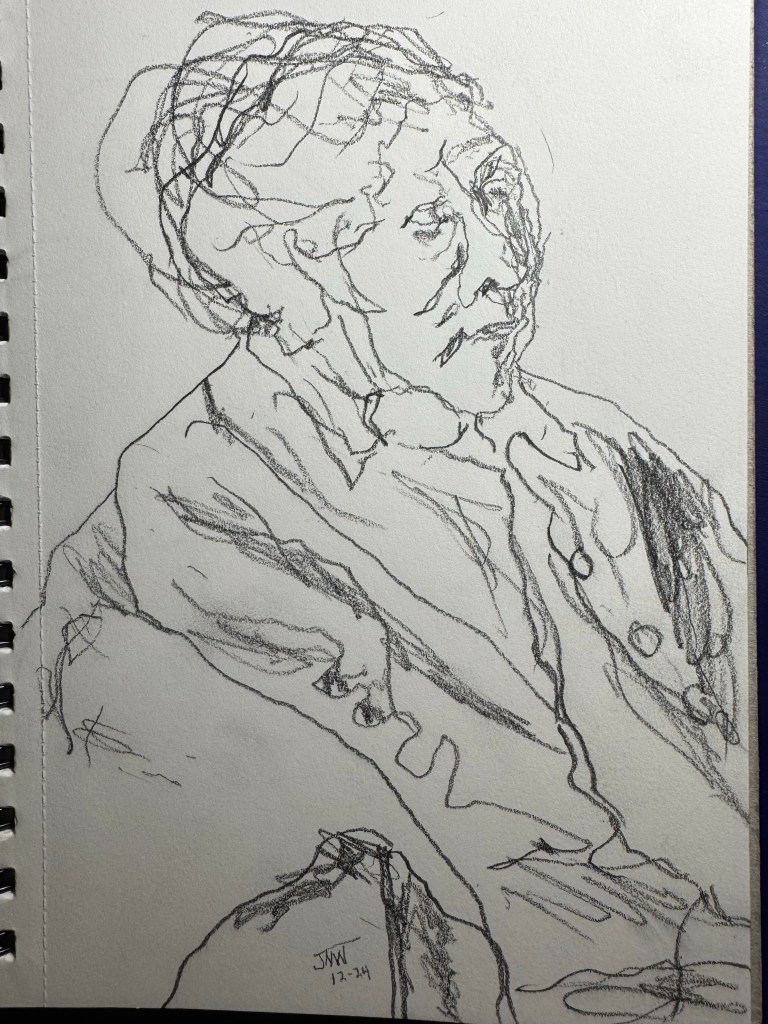

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Gracias por compartir la belleza. Me ha encantado, no creo que haya un momento en el día que supere esta lectura.💐💐💐

LikeLiked by 2 people

Me siento colmado de un elogio que no sé si lo merezque, pero lo recibo con sumo agradecimiento. Me ayudas a pensar que procurando expresar cómo y por qué un texto me conmueve tal vez tenga su valor. ¡Muchas gracias, y un saludo cordial!

LikeLiked by 1 person