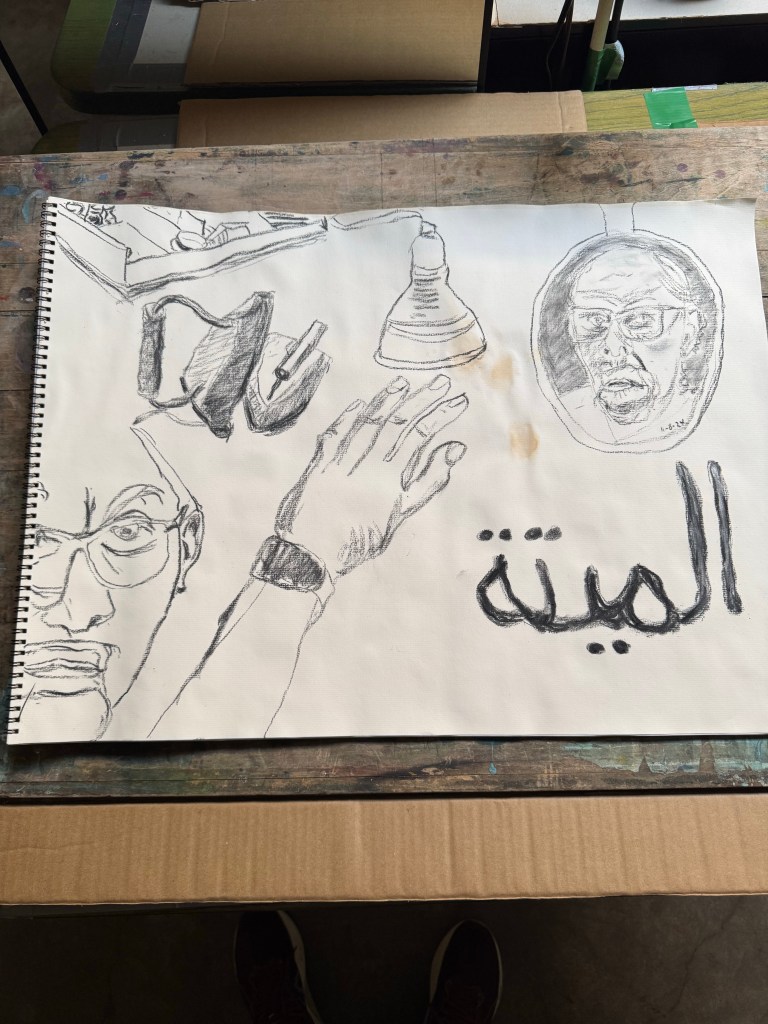

I’m to draw what I find interesting in front of me; what I can perceive to be of interest; what I can make interesting. It’s a confrontation between two undisciplined hands, two bespectacled eyes, and the naked reality of a surrounding, tridimensional soup. “Disquieting” isn’t the half of it. I’ve long dodged the hard work of learning to draw freehandedly, a project which is advanced by — wait for it — practice. A mentor pushes me to overcome my terror of the unguided line. I covenant uneasily with myself to share the outcomes such as (alas) they are. The face I see in the mirror and what lands on the tablet share no resemblance. But I’ve no urge to do self portraiture anyway; were there another live face in the house I’d happily draw it instead. Just yesterday I learned the hard way what my mentor warns against, which is overworking a drawing. The face sketched in several minutes had achieved a certain — what shall I call it? — intact quality, not skillful but at least stable, flawed in a forward direction. Should’ve stopped there. Didn’t. So it goes.

“If all men are born free, how is it that women are born slaves?”

(Mary Astell (1666-1731)

The question of Adam’s and Eve’s navels has been discussed by theologians. It’s interesting, some have thought, for how it bears on the matter of their having come into being through other than a birth canal. I’d never thought of the anatomical detail until its mention on a BBC4 podcast. Religions go where reason deigns not tread.

While talking poetry, I’d like to pay my respects, in one swell foop, to Poetry, November 2024. First, check out the cover, whose credit goes to Andrea Trabucco-Campos. The magazine has adopted a clever, standardized design of its name. The ingenious objectifying of that design on the current cover is highly satisfying.

Jane Hirshfield’s two poems communicate phenomenal directness on their surface. As I read them the term “plainsong” kept circling my mind. They jolted me out of my cynicism that poetry can’t lift me out of my chair immediately. In the poem titled “I am asked a question,” it’s “life” doing the asking. The respondent suggests a better question, one I like more the sound of, / with more pleasing grammar; note the slightly atypical word order of “one I like more the sound of,” as if the dialog with life were conducted in a non-native tongue. The poem shrugs off completely the project of answering any question. Whatever was asked is rightly unstated: life states itself. The speaker’s Candide-like resort to tending garden, practically and spiritually, is its own answer; that, and submission to the act of observing.

I leave the question.

I go into the garden and weed.

My life weeds with me.

The knees of my pants are stained.

Hirshfield’s second poem’s title is elegantly un-plain, highflown: “I Was Not, Among My Kind, Distinctive.” A mid-passage, and the poem’s conclusion, show how distinctively it’s knit.

First, the mid-passage, where postpositive, adverbial, subordinate clauses with elided predication administer a happy shock:

My left hand believed it could hold my right

when the hammer.

My right hand believed it could hold my left

when the fire.

The theme of trial and failure runs quietly through the poem, including this perfect lone hexameter: I failed to reach my sister’s hand before she died.

Now the conclusion, where the poem comes to a self-knowing sort of rest:

Distractions: ordinary. Omissions: rampant.

Thinking any of this peculiar to me.

No, I was not distinctive, among my kind.

Showered with pollen, I sneezed.

I ate, and by morning found myself once again hungry.

Hirshfield treats deep thoughts with straightforward syntax in her poems. By contrast, the issue ends with two essays full of jazzy riffs, impudent juxtapositions and sinuous syntax such as one might expect to be strewn with line breaks or printed depictively. It’s how poets juice spitballing in prose with their versions of insightfulness.

Antipathy can be an act of discernment, of love, a challenge to readers, a push against them that can paradoxically bring them closer… I want reading a poem to be a bit like risky sex, the kind when, after X leaves, I turn on the bright bedroom light to check for choke marks. But the choking felt so good.

(Randall Mann, “On Contempt: I Want to Be Liked”)

Maybe pettiness means not even giving what isn’t yours. And the half-life of pettiness? It may be the bismuth of emotions, the clusterfuck of them.

(Andrea Cohen, “On Pettiness: About Those Flying Buttresses”)

Though it technically denotes standoffishness, I like the word “offishness,” to which Sianne Ngai draws our attention in the “Irritation” chapter of her book Ugly Feelings, as a way to describe how poems like “The Fish” — though I can think of no other poem “like” “The Fish” — deploy a kind of distance in their manner that, while felt intensely, can also be crossed almost instantly.

(Graham Foust, “On Irritation: Itching, Scratching, Swelling”)

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Nice to see you drawing, and reading, and questioning and thinking … and blogging!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Sue! Greetings from here.

LikeLiked by 1 person