In an essay, Meghan O’Rourke writes the following:

Ambivalence is, like so much poetry, paratactic. (Poetry, June 2024)

Ambivalence is a state of mind characterized by mixed feelings. Parataxis is a rhetorical move. It daisy-chains independent clauses, leaving it to the reader to intuit their relationships. I came. I saw. I conquered. Its opposite, hypotaxis, introduces dependent clauses into the mix, which “can bolster the meaning of a work.” Poems forego such bolstering by flaring off fussy back story.

O’Rourke invites attention to the ending of a famous Frost poem — never mind which one. She focuses on the line break which repeats “I“ across the enjambment. “These final rousing lines enact a kind of ambivalent epistemic stutter… that often goes unremarked,” she writes. If all that can be said about the choice not to lead a certain existence is that it “has made all the difference,” that line is “trickily ambivalent: is the difference good or bad?” she muses.”

Would “trickily ambiguous” have been a better descriptor of Frost’s line? (I hear you say it’s a distinction without a difference.) In distilling its contemplations, poetry augments cognitive load on the reader. In the best of cases it earns the right to do so; the reader’s exertions add value to the poem. Hell, let’s agree on this: A poem without a good reader is a breathless tuba.

Here’s where I land on the epistemic stutter gone unremarked: Frost doesn’t need for us to know. Or rather, Frost needs for us not to know. Imagine he had jotted the following in a pocket notebook where he kept his ideas:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I stood contemplating which one to take. One looked heavily traveled, judging by the ruts; but the other path looked as if it hadn’t been traversed in months, which appealed to my instinct for discovery. I took the one less traveled by, because I was footloose and fancy free back then — just wanted to stretch my wings and see some country — and that has made all the difference. Why and how? Because I met my future wife when I spent the night in that little lodge on Lake Pottawatomie. If I hadn’t made that flippant decision to go one way and not another, I wouldn’t bask in the love of that good woman today.

Now imagine the road taken.

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Protect the Rim, Kill the Note

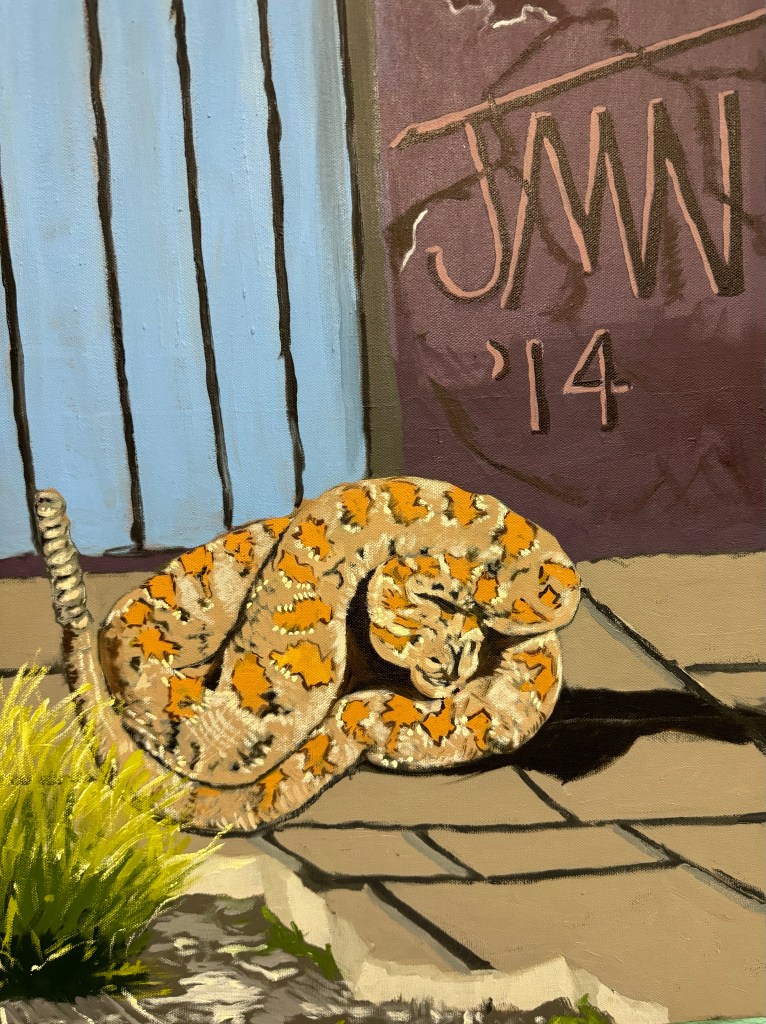

I got a charge out of Ernie Barnes’s painting titled “Protect the Rim.” The surreally long figures, the lofty rustic hoop, and even the knocked-together frame all have a quirky charm.

In a parallel world, my grandmother’s capacious lungs powered Sundays in my childhood church. Her soprano anchored the choir and was audible from the street. Michael Frazier’s feisty “Mom” reminded me of her.

At Church, I Tell My Mom She’s Singing Off-Key and She Says,

I ain’t off-key. I just stepped out the key

so when I return

you can understand the key a little better.

The preacher isn’t the only

teacher. Why hit a note on the head

when I can kill it? You mean to tell me

you come here week after week

and want the same old Amazing

Grace? Just cause the Blood will never lose its power

don’t mean a melody won’t.

My ministry may not be song, but I got a song

to sing. I done made it from Sunday

to Sunday. You expect me not to celebrate

and thank God, with my hands raised,

my flats off, my full and open

throat?

(Will Heinrich, “Ernie Barnes Paints What It Feels Like to Move,” New York Times, 5-30-24,

Michael Frazier, “At Church, I Tell My Mom She’s Singing Off-Key and She Says,” Poetry, May 2024)

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved