The Greek derivatives in English spurt from a font of abstruse vocables that gives us, say, “dithyramb” — “a passionate or inflated speech, poem or other writing.” It’s a short hop to coinage such as “pithyramb” — “a passionate or inflated instance of pith” — proffered by… wait for it… a “pithyrambo.”

Take Hemingway, whom many of us cite unread. One of his characters says something like “bankruptcy comes on gradually, then all of a sudden.” A certain Ms. Clausing quoted in The Times pithyrambed it shamelessly:

… Ms. Clausing, the U.C.L.A. economist, warned against assuming that just because Mr. Trump’s policies haven’t harmed the economy yet, they never will. “The long run takes a long time to arrive, and when it comes it comes with astonishing swiftness,” she said.

As we await the long run’s arrival let’s kill some time tinkering with Woody’s ditty:

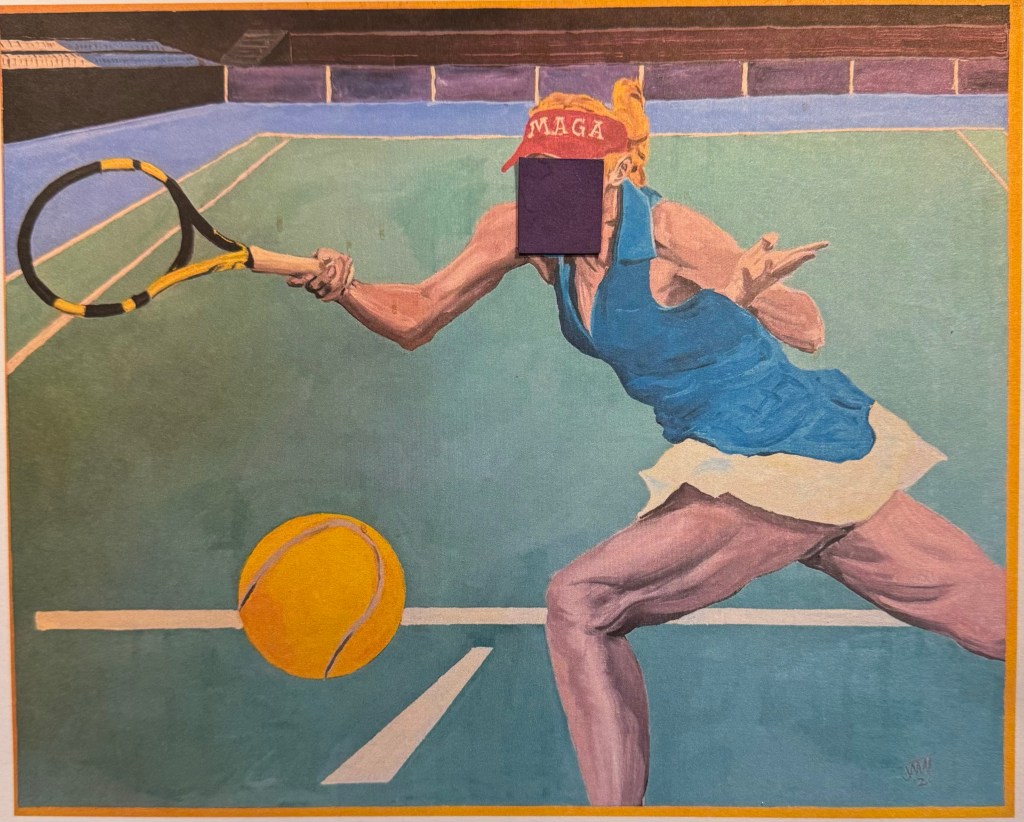

THIS LAND IS OUR LAND

(Call and Response)

This land is our land

(That land is our land)

From th’ shores of Green Land

(To th’ Cuban Eye Land)

From fair New Found Land

(Where’er we lay hand)

To th’ Hemisphere’s End

(Or where our troops land)

Your land is our land

(There is our Home Land)

(ICE Land is MY Land)

(Mar-a-La-GO-Land)

All real estate grand

(A place to grandstand)

Snooty Switzer-land

(Little Saint James Land)

All mine to COM-mand

(Kiss thy behind land)

The former Rhine Land

(All thine to DE-mand)

(c) 2026 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Three Rules With Tolerances

ḍaḥik-nā ḍiḥkaẗ(an) ka-l-ẖamr(i) “We laughed a laughter like the wine.” The phrase is from a poem by Haidar Al Abdullah titled Tarajjal yā ḥiṣān. I like to translate the title as “Make Like a Man, O Horse,” and the phrase more freely as “We spilt laughter like wine.” Their respective published translations by Yaseen Noorani are Go Dismounted Like a Man, Horse and We let out a vinous peal of laughter. (From Tracing the Ether: Contemporary Poetry from Saudi Arabia, ed. Moneera Al-Ghadeer, Syracuse University Press, 2026.)

RULE OF GOLD

Treat others like you want to be treated.

RULE OF IRON

Believe in Me or else.

RULE OF THUMB

Steer into the skid.

TOLERANCES

“Every trade works to different tolerances. Steel workers aim to be accurate within half an inch; carpenters a quarter of an inch; sheetrockers an eighth of an inch; and stone workers a sixteenth.”

(Burkhard Bilger, “The Art of Building the Impossible,” The New Yorker.)

(c) 2025 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved