Emilie Moorhouse’s translations of the verse of Joyce Mansour (1928-1986) in Poetry, June 2023, give full-throated voice to the satisfactions of the originals.

Take the line from “Fever your sex is a crab” that serves as my title: Lack of good judgment would make me argue for “The avidity of your man-eating membranes” over “The eagerness of your cannibalistic tissues,” which is Moorhouse’s civilized rendering.

“Muqueueses” is a hairy caterpillar of a word, a phonological jamboree oozing with vowels, glorious as French can be. I love saying “muqueuses cannibales,”talking about saying it, imagining being heard doing so.

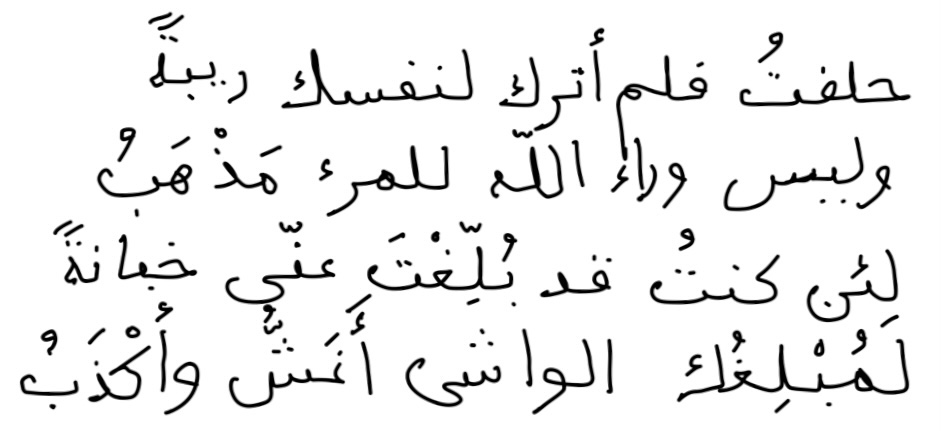

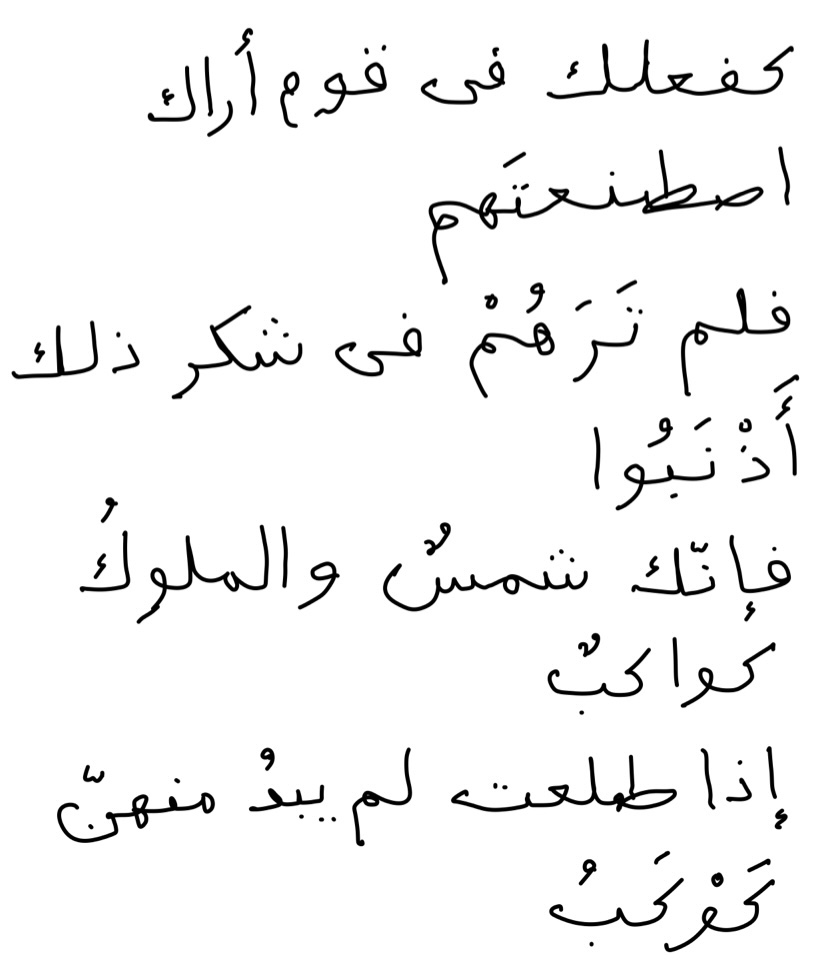

Mansour’s language seems notably “musical” to my ear, not tinkly but savage. A pleasurable aspect of reading the poems alongside their translations is savoring their acoustic power while leaning confidently on Moorhouse for help with unfamiliar words. The bolded terms in the extract below were new to me:

Rhabdomancie

…

Puis affalée dans l’armoire près du lit

Projetez votre oméga plus une poignée de salamandres

Dans le miroir ou l’ombre se dandine

…

Taquinez ses penchants avec un blaireau de soie

Saupoudrez son phalène de sang et de suie

…

Malgré moi ma charogne fanatise avec ton vieux sexe débusqué

Qui dort.

Dowsing

…

Then sprawled in the armoire next to the bed

Project your final word along with a handful of salamanders

In the mirror where the shadow sways

…

Tease his kinks with a silk brush

Sprinkle his moth with blood and soot

…

In spite of myself my carrion fanaticizes over your ousted old cock

That sleeps

This writing seems very current though its author died over 3 decades ago. It conjures words going for a walk as Klee took line for a walk. The sensuous fact of themselves is that to which they lead, and what they share with dream is the quality of slipping capture.

What does “surreal” mean, anyway, to a lay reader of today? It’s easy to call much contemporary verse surreal insofar as it doesn’t “make sense” in the ordinary way, doesn’t correlate to realities that are objective, if that means perceptible or conceivable in an awake, reasoning state of mind. I thought perhaps that’s what Eliot meant by “objective correlative,” but a quick Wiki-dip reminded me that what he meant was too abstruse to be memorable.

(c) 2023 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

A Compelling Rationale for Taking Up Versifying

Monet fondly recalls her former college adviser: “I remember her suggesting what schools to go to and it wasn’t Harvard, you know what I mean?”

I think I know what she means. It’s just as well. The Harvard English department has dropped its poetry requirement for an English degree.

Monet’s YouTube video, The Devil You Know, serves up sensory tumult ending with an affecting diminuendo dissolve. Memorable line:

Silence is a noise, too.

I also relish the phrase “word-workers” among her honor roll of callings in the video. I could wish only that Monet’s word work were slightly more audible amidst the lively instrumentation that includes the sterling horn of Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah.

Sources

Marcus J. Moore, “Aja Monet, a Musical Poet of Love,” New York Times, 6-8-23.

Maureen Dowd, “Don’t Kill ‘Frankenstein’ With Real Frankensteins at Large,” New York Times, 5-27-23.

(c) 2023 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved