“Island of the Cyclops: The Early Years” (2018) by Eric Fischl. Credit… Eric Fischl. [New York Times caption and illustration]

[Eric Fischl] “Eric Fischl: Stories Told”

Featured here are about 40 large-scale works by the figurative painter Eric Fischl, created from the late 1970s to today. The artist largely had to teach himself traditional painting styles, studying early modern artists like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, because new art forms ruled during the ’70s and classic movements were out of fashion…

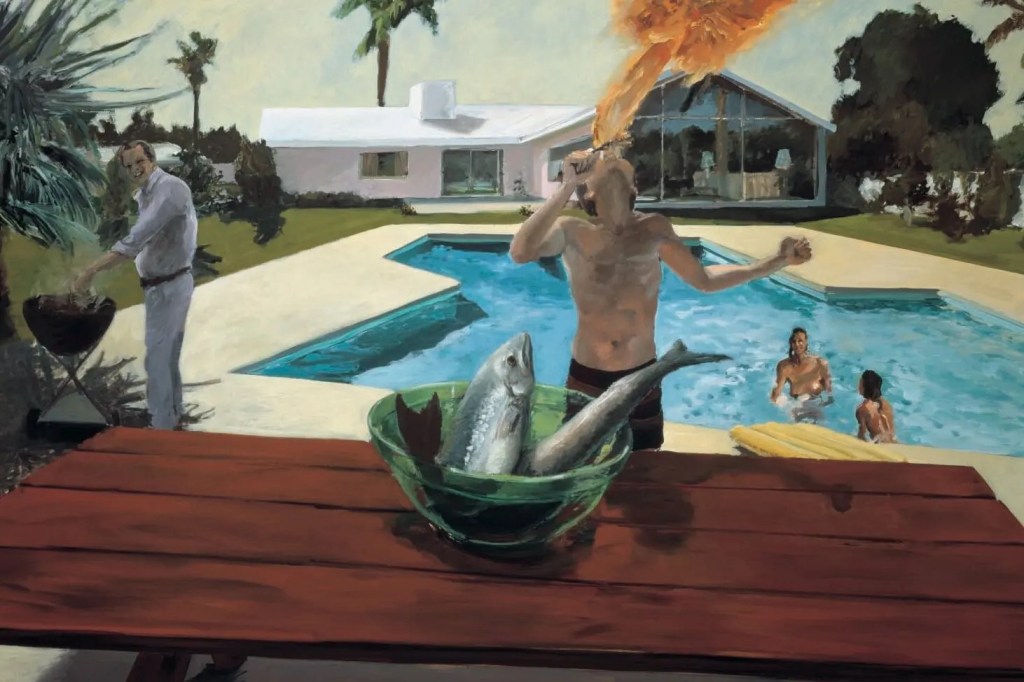

“Barbeque” (1982) by Eric Fischl is part of the exhibition “Eric Fischl: Stories Told” at the Phoenix Art Museum. Credit… Eric Fischl. [New York Times caption and illustration]

[Monica Thompson] “Threads”

A selection of collages, assemblages, textiles, eco-prints and weavings created by nine Montana women who are artists, mothers and art teachers is presented here…

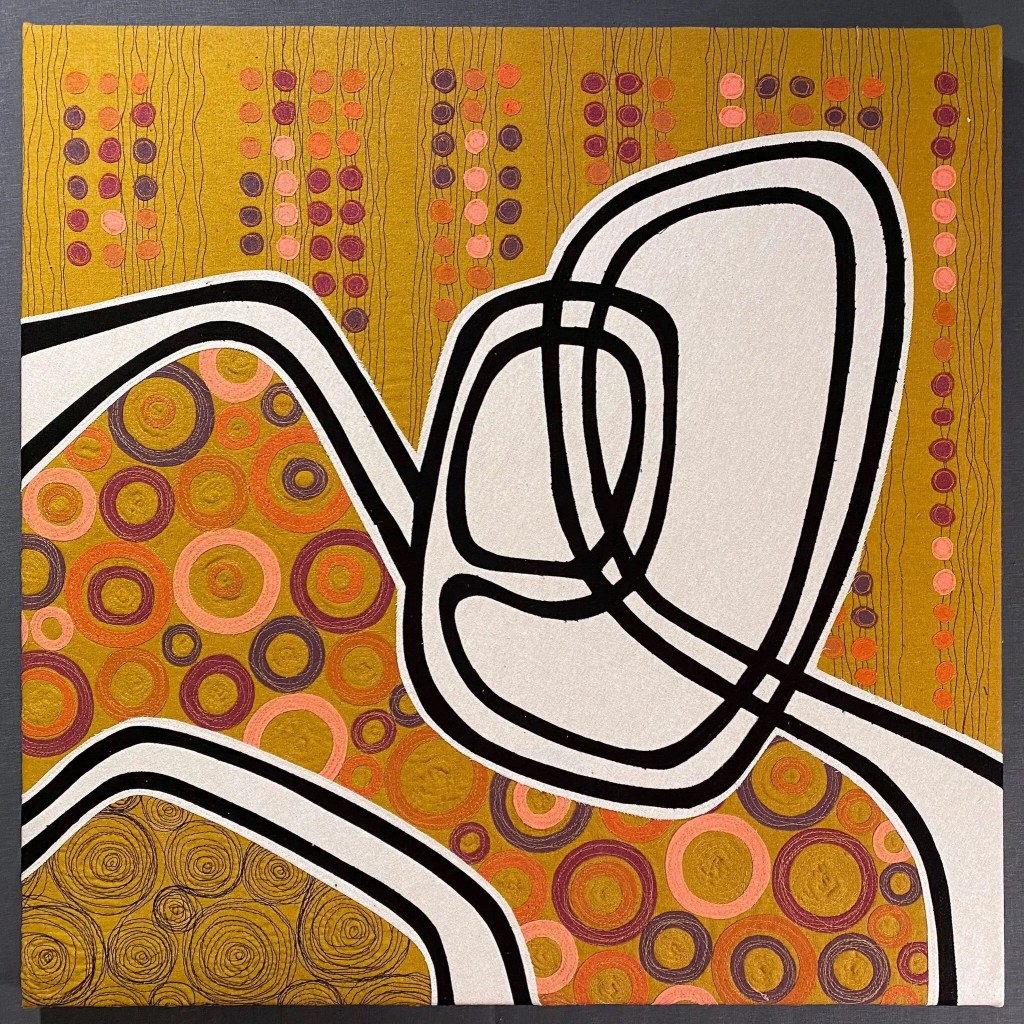

“The Greater the Whole” (2023) by Monica Thompson. Credit… Monica Thompson, via Yellowstone Art Museum. [New York Times caption and illustration]

[Uman] “Uman: After all the things …”

The artist Uman was born in Somalia and raised in Kenya. She spent her teenage years in Denmark and then ultimately landed in upstate New York… Her paintings, created with markings like spirals, doodles, circles and stars, evoke the fabrics worn by women in Somali bazaars, the slanted flourishes of Arabic calligraphy and the countryside of Kenya and upstate New York…

“Sumac Tree in Roseboom” (2022-23) by Uman. Credit… Lance Brewer[New York Times caption and illustration]

“Eedo Kafia’s Turkana” (2024) by Uman. Credit… Lance Brewer. [New York Times caption and illustration]

All excerpts and illustrations are from Morgan Malget, “A Full Season of Art to See at Museums and Galleries Across the U.S.,” New York Times, 10-11-25.

(c) 2025 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

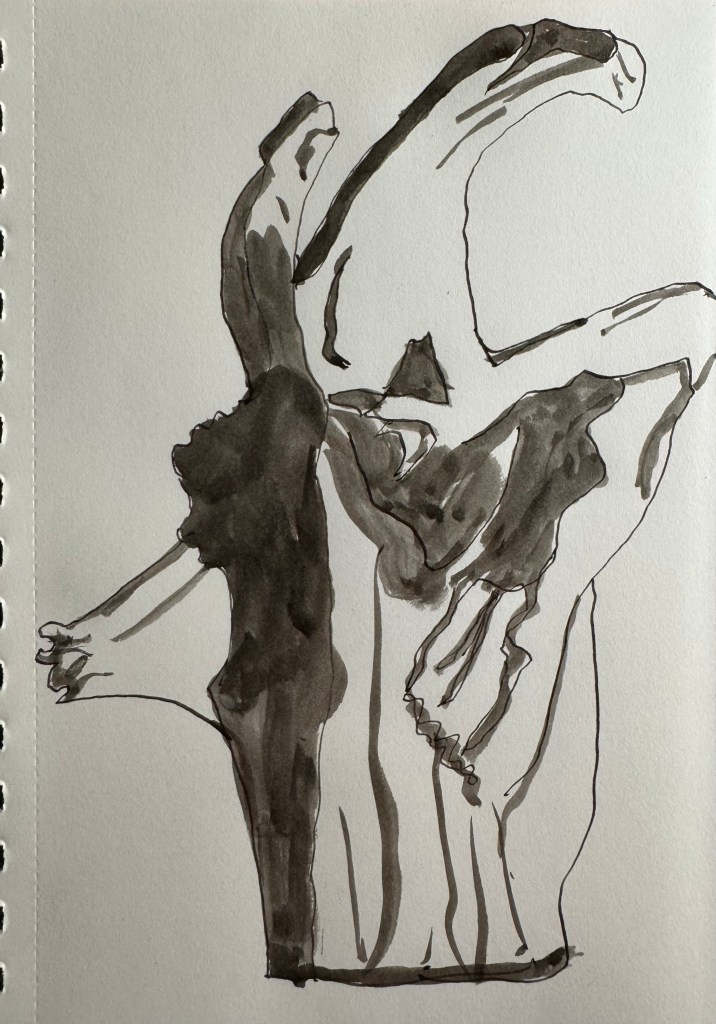

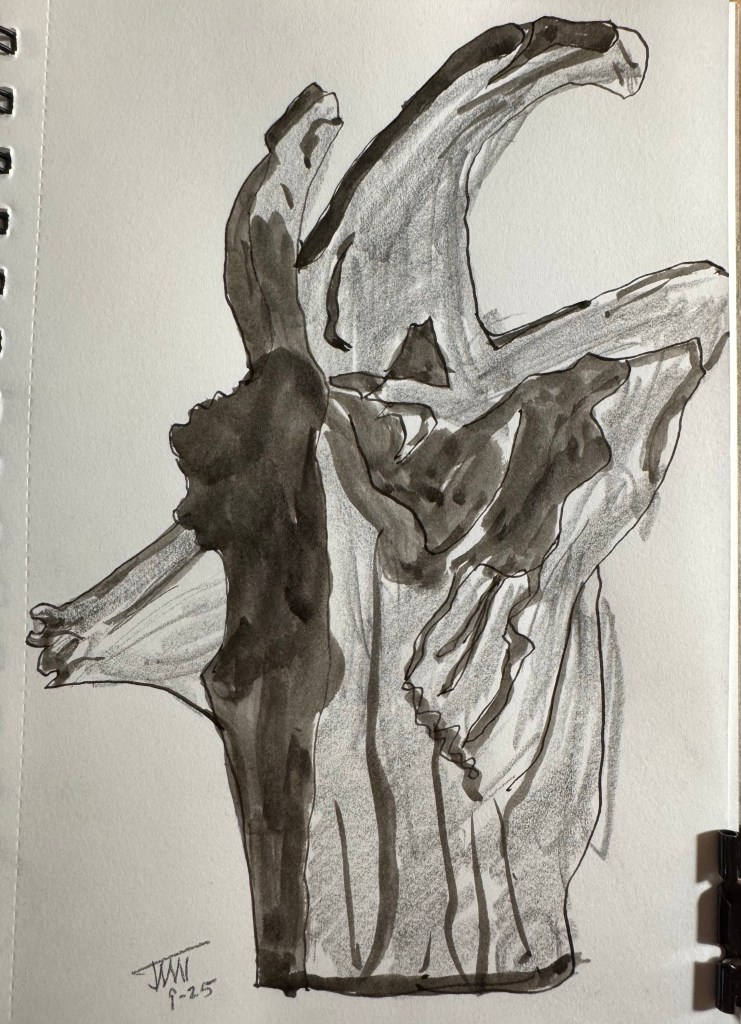

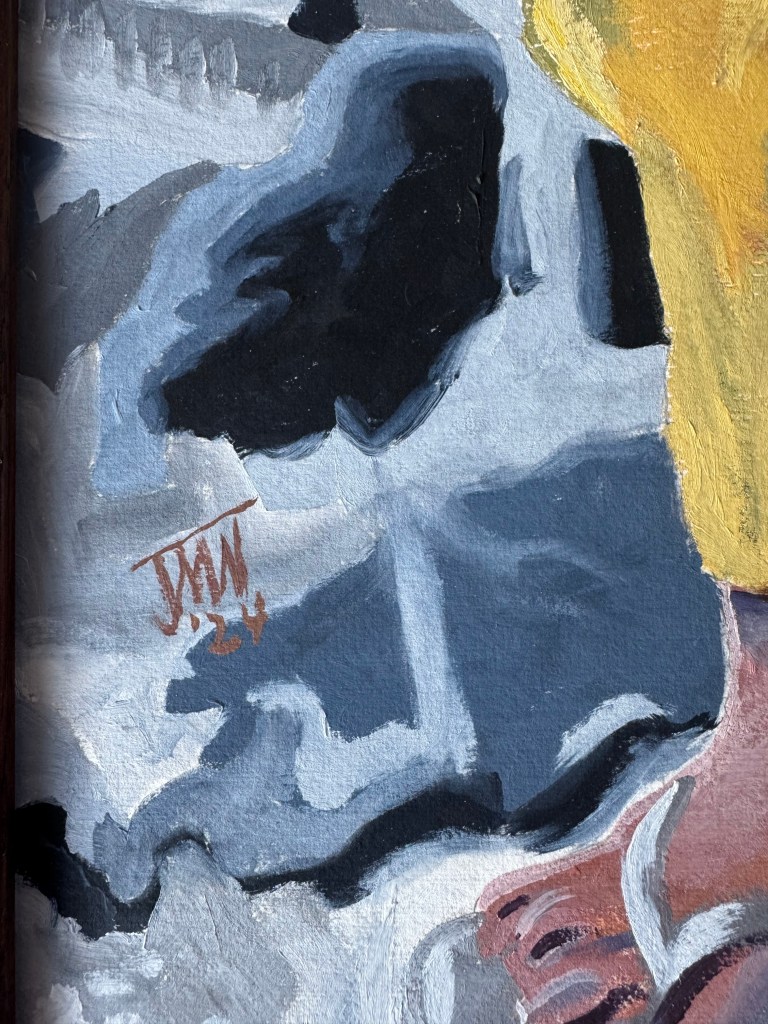

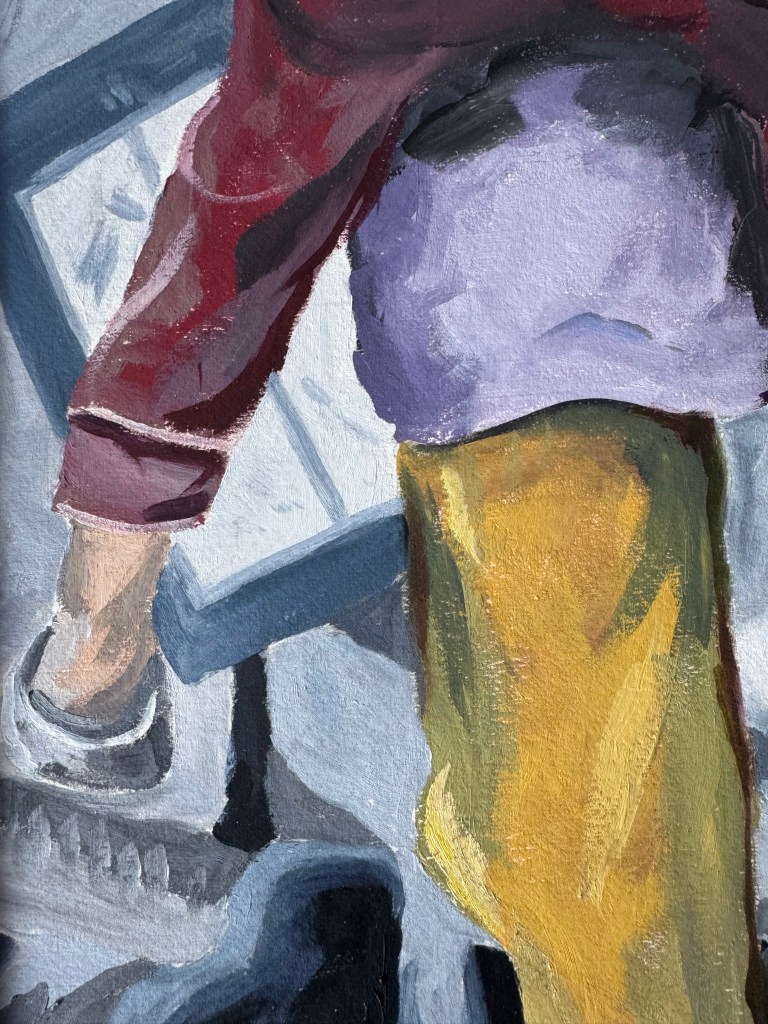

A Poem Is a Sketch

A friend I’ll nickname Stardust, avid prose reader, has remarked that relatively few people have a taste for poetry nowadays. I surmise it’s always been so, even in this or that era when <name-your-Great-Poet> flourished. The Great One would have been lionized by a coterie of fans in a populous land of nonreaders.

Poets are a few obsessives bent on strewing words just so, in a way the next person can’t, applecart-tipping and necessary. Their readers are a peculiar lot bent on stewing over those words. I like to think of doggerel, tangentially, as poetry’s running dog. Hail to thee, blithe mutt! Bird thou never wert.

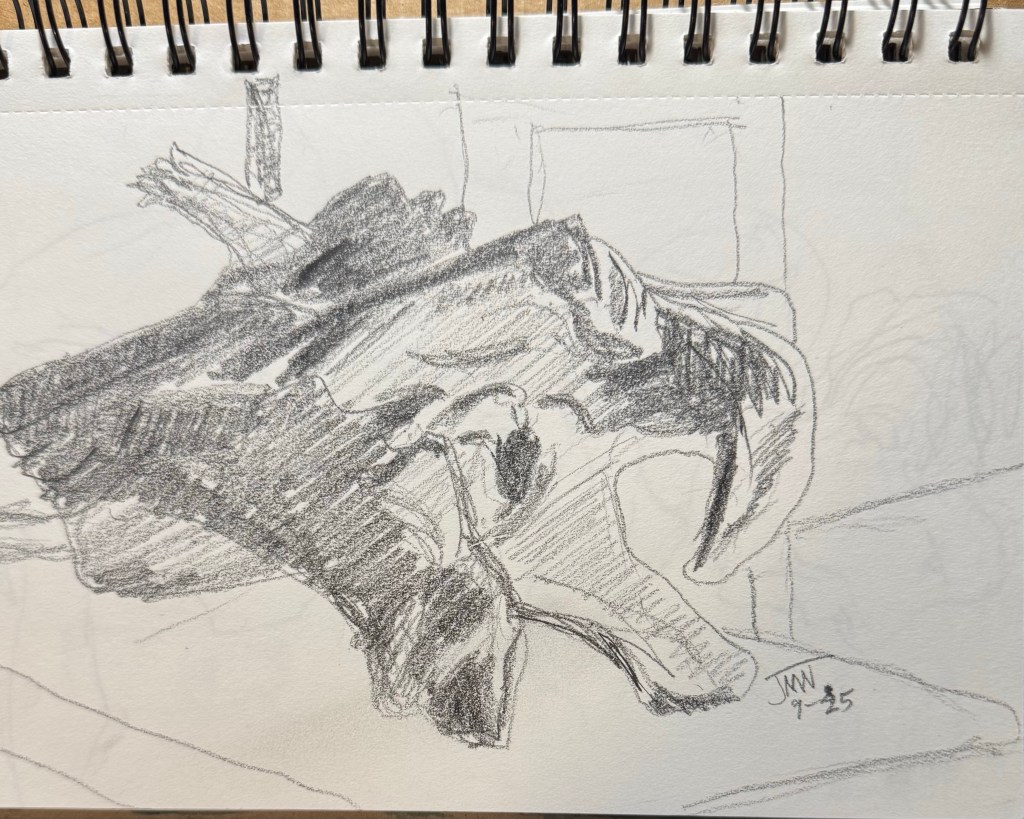

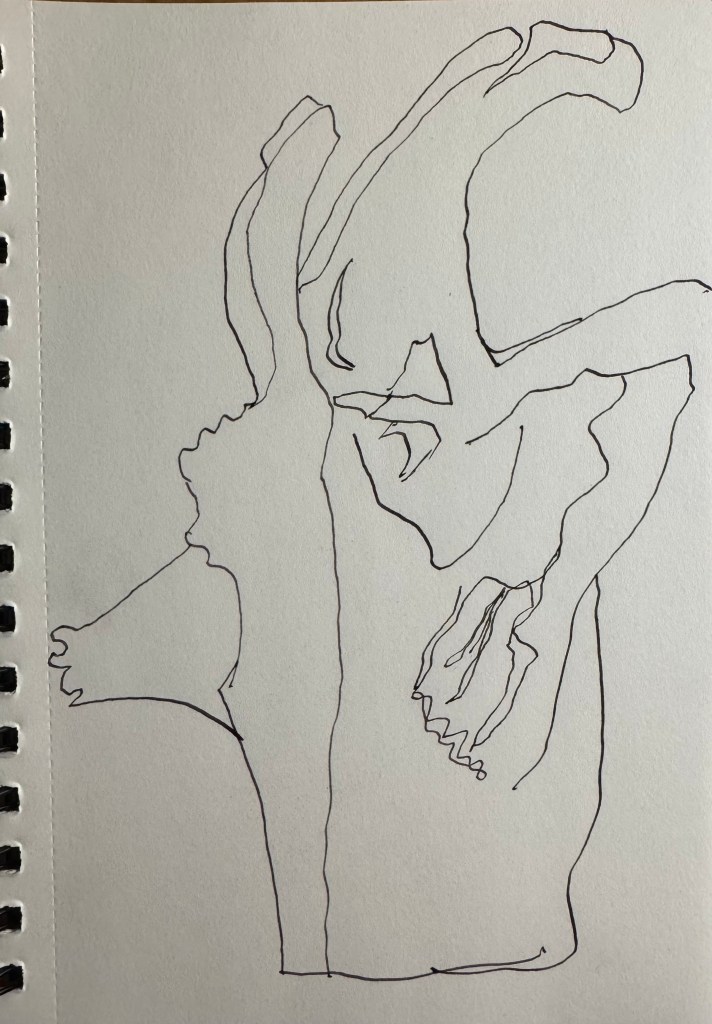

The pivot point in this spiel is that Stardust is a skilled artist who can reify in line, value and hue what a poet does in words:

I did not want / the moment to end / then stopped wanting / so I could / be, not yearn,…

(Lia Purpura, from “Intersection”, Poetry, September 2025)

“Did not want… then stopped wanting… be, not yearn,” Impossible to say differently that’s better. Both Stardust and Lia Purpura can turn a flash of perception into a thing that lingers, and completes itself in the psyche of another human.

If Stardust is ever pierced by a poem-moment, and there’s no special need for that to happen from where I stand, there’s hundred’s of feet of fertile loam accrued in my friend’s delta of sensibility for it to root in. Stardust will have perceived the poem as lines, akin to a sketch that works unusually well.

(c) 2025 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved