In a dispute with the EU, AstraZeneca’s CEO insists their contract requires only “best reasonable efforts” to meet delivery schedules.

Lawyers disagreed over the language of the E.U. contract, which was only partly made public.

(Steven Erlanger and Matina Stevis-Gridneff, “E.U. Makes a Sudden and Embarrassing U-Turn on Vaccines,” NYTimes, 1-30-21)

Is the dispute over language about style or about grammar? Surely what the words actually say can’t be in contention?

Contracts, after all, are drafted with consummate clarity by highly literate lawyers. Then they are read and vetted exhaustively by all parties prior to the signing.

Of course my comments are crapulent with irony and contrariness to fact. Any agreement that includes phrases such as “best reasonable efforts” is designed (by lawyers) not to be load-bearing or fit for purpose.

For contrast, a doctor commenting on the Johnson & Johnson Covid vaccine says its promised reduction in severe disease is a powerful selling point.

“That’s what you want… You want to stay out of the hospital, and stay out of the morgue.”

(Denise Grady, “Which Covid Vaccine Should You Get? Experts Cite the Effect Against Severe Disease,” NYTimes, 1-29-21)

No mention of “best reasonable efforts.” Just consummate clarity: Stay out of the morgue.

(c) 2021 JMN

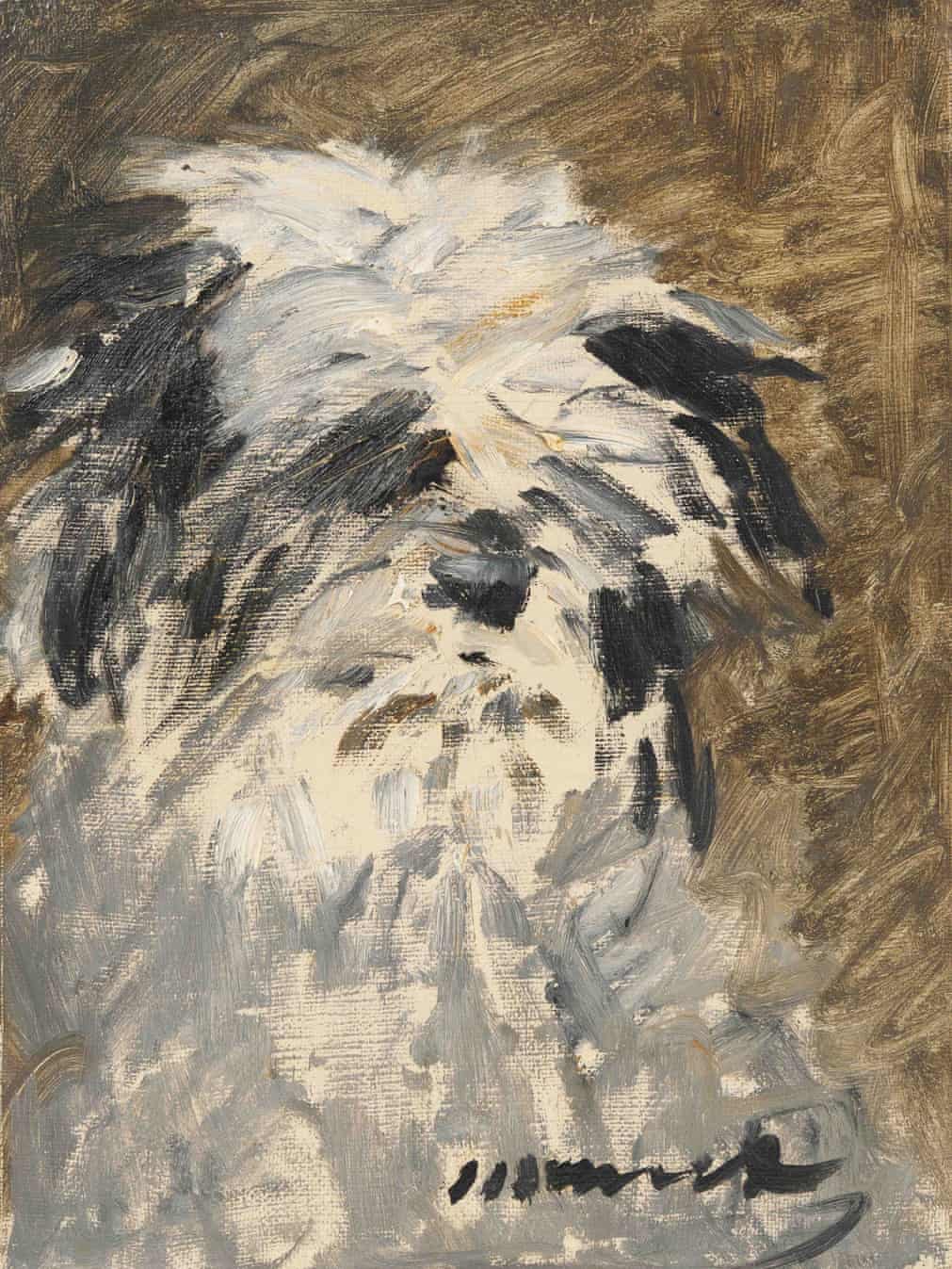

Harold Johnson Nichols, ca. 2005.

Harold Johnson Nichols, ca. 2005.

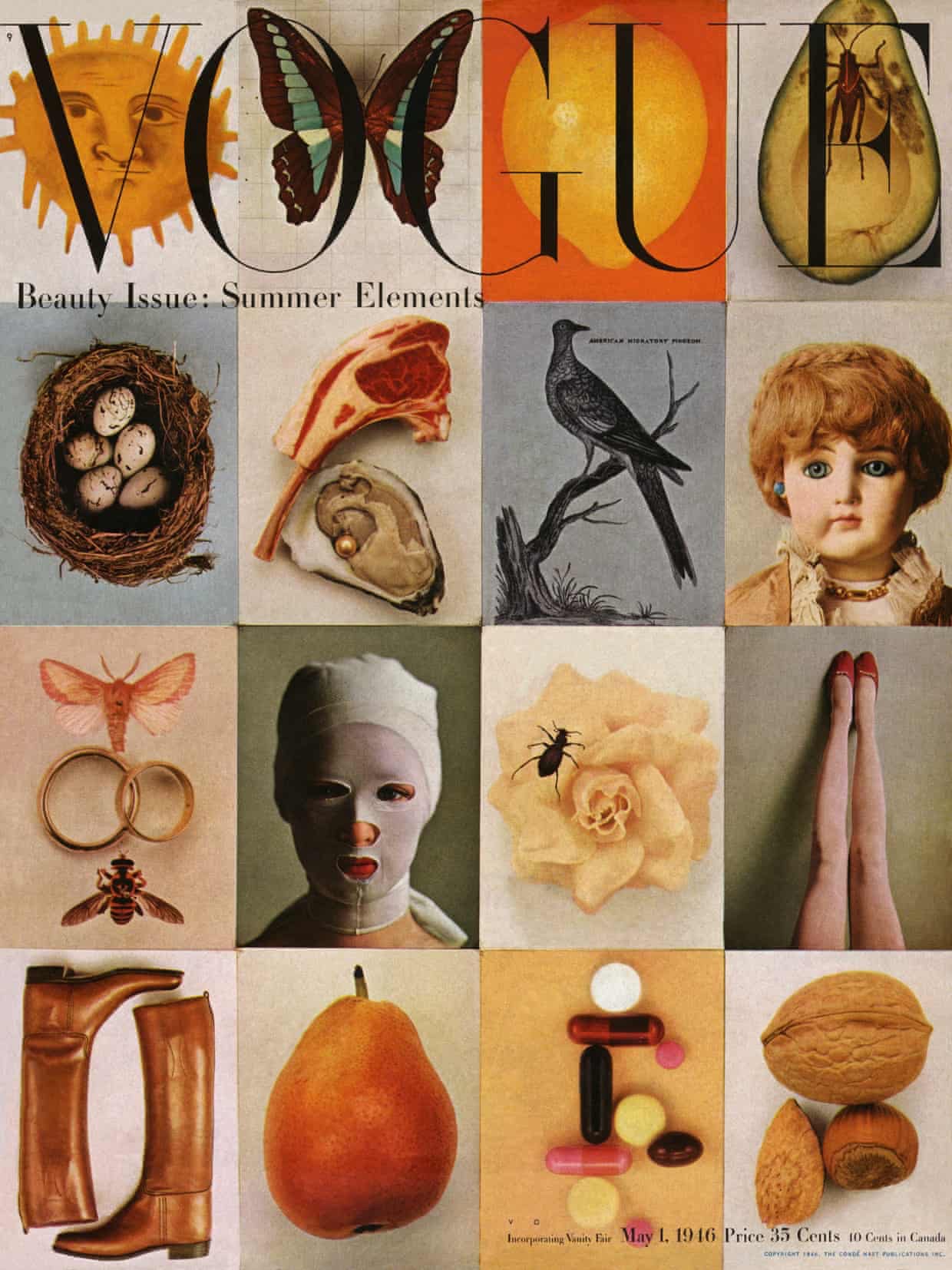

‘Certitudes’

This is the Cubist revolution: Here, for the first time in Western art since the Renaissance, the world as we see it no longer has primacy. The picture is no longer an act of perception. It’s an act of imagination, with a life and a logic of its own.

Yet Cubism got so analytical that it nearly lost all legibility. To avoid becoming totally abstract, it needed what Braque called certitudes: recognizable hooks from modern life.

(Jason Farrago, “An Art Revolution Made With Scissors and Glue,” NYTimes, 1-29-21)

Farrago’s latest entry in the NYTimes’s ingenious “Close Read” series focuses on Juan Gris’s “Still Life: The Table” (1914).

My first response to Farrago’s elegant art talk is almost always “Well said!” His language sweeps me up.

Then, often as not, there follows a moment of “Wait! But…?” It’s when the faculty that tests pretty words, mindful of my weakness for them, kicks in, and plainer words come to mind.

If the world as we see it no longer has primacy, then depiction presumably gives way to something less — shall we say “realistic,” to use a layman’s term?

Saying the picture is an act of imagination and not perception seems to press the point rather hard. I think perception remains. Could we not say, rather, that the Cubist picture is an imaginative rendering of what’s perceived?

In observing Gris’s still life, Farrago is indeed at pains to point at, and name, the many perceived facts — bottles, newspapers, book, cigarettes — that the painter cleverly incorporated into his collage. They are Braque’s “certitudes.”

It’s a wonderful term, “certitudes,” perhaps my favorite takeaway from the essay. They are the “recognizable hooks from modern life” that helped Cubism stay “legible.”

(c) 2021 JMN