[Translator’s note: The blog of Andrés Cifuentes — Eco Social…Ojo Crítico (doff of cap to) led me to this poem by Miguel Hernández. It doesn’t soar as poetry, but it does register a raw and memorable cri de coeur. All translations fail, and mine does so by indulging in flights of paraphrase to offset the flatness of affect of the literal English. JMN]

Cowards

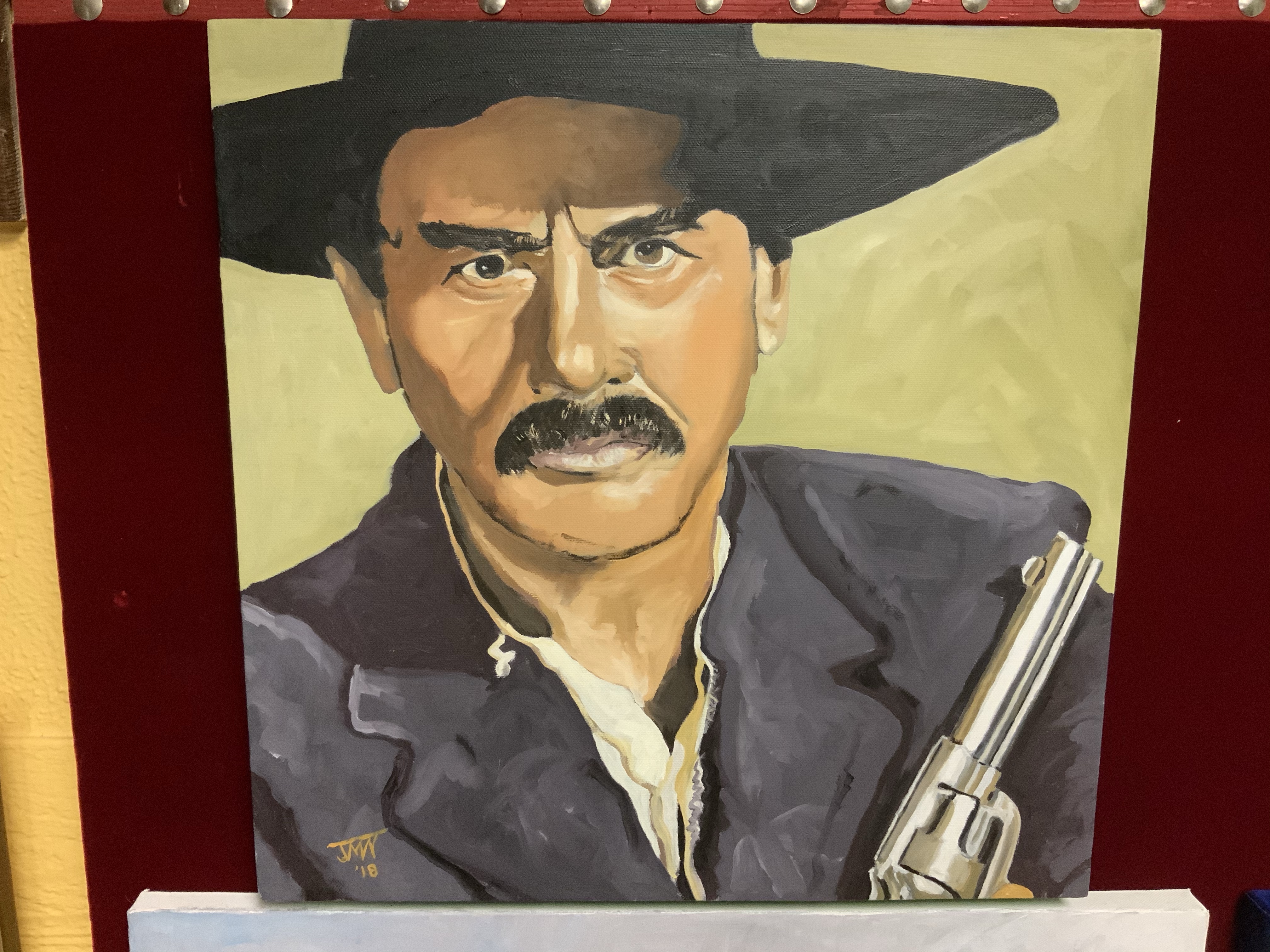

Men I see who of manliness

have none but what they flaunt,

the look and the Marlboro,

the britches and the beard.

At heart they are bunnies,

chickens in their guts,

hounds quick at crapping,

barkers in peace time

who in cannon season

vanish from the map.

These macho cottontails,

commissars of retreat,

hearing miles away

the thunder of bullets,

like matchless heroes

cut and run for the hills,

shitting explosively,

hair standing on end.

Bravely they take cover,

gallantly abandon

the blast radius,

these turds on the run

who’ve kicked for ages

my soul in the balls.

Where will you end up

that’s not dead, paleface rabbits,

untrustworthy curs

with extra paws?

Aren’t you ashamed to see

to this extent in Spain

so many steady women

under so much threat?

A bullet for every tooth

is what your life deserves,

cowards wearing coward hides

with reeds for hearts.

You tremble as if gripped

by a century’s worth of frost

and fade from sun to shadow

quaking in your boots.

For you a basement’s

undefended by its house.

Your yellow streak begs everyone

for battalions of walls

and lead barriers rimming

cliffs and trenches,

saving our threadbare lives

mired in gore and dread.

Not enough for you, defense

by showers of noble blood

shed unstintingly

abundant and warm

day in, day out,

onto Castilian clod.

You’re senseless to the calling

of the splattered lives.

To keep your pelts intact

burrows and dens won’t do,

not rabbit holes,

not toilets even, nothing will.

You flinch and flee, which gives

the people you turn tail on

just cause to drill

your disappearing backs with lead.

Only men alone remain

in the heat of battle,

and you, from far away,

try to rouge your infamy,

but the pallor of cowardice

will not wipe off your faces.

Keep standing your pathetic posts

over your pathetic cobwebs.

Swap your weapon for a broom,

and sweep with your ass cheeks

the caca you leave behind

wherever you set foot.

Wind of the People, 1937

Miguel Hernández

English version by JMN

Los cobardes

Hombres veo que de hombres

solo tienen, solo gastan

el parecer y el cigarro,

el pantalón y la barba.

En el corazón son liebres,

gallinas en las entrañas,

galgos de rápido vientre,

que en épocas de paz ladran

y en épocas de cañones

desaparecen del mapa.

Estos hombres, estas liebres,

comisarios de la alarma,

cuando escuchan a cien leguas

el estruendo de las balas,

con singular heroísmo

a la carrera se lanzan,

se les alborota el ano,

el pelo se les espanta.

Valientemente se esconden,

gallardamente se escapan

del campo de los peligros

estas fugitivas cacas,

que me duelen hace tiempo

en los cojones del alma.

¿Dónde iréis que no vayáis

a la muerte, liebres pálidas,

podencos de poca fe

y de demasiadas patas?

¿No os avergüenza mirar

en tanto lugar de España

a tanta mujer serena

bajo tantas amenazas?

Un tiro por cada diente

vuestra existencia reclama,

cobardes de piel cobarde

y de corazón de caña.

Tembláis como poseídos

de todo un siglo de escarcha

y vais del sol a la sombra

llenos de desconfianza.

Halláis los sótanos poco

defendidos por las casas.

Vuestro miedo exige al mundo

batallones de murallas,

barreras de plomo a orillas

de precipicios y zanjas

para nuestra pobre vida,

mezquina de sangre y ansias.

No os basta estar defendidos

por lluvias de sangre hidalga,

que no cesa de caer,

generosamente cálida,

un día tras otro día

a la gleba castellana.

No sentís el llamamiento

de las vidas derramadas.

Para salvar vuestra piel

las madrigueras no os bastan,

no os bastan los agujeros,

ni los retretes ni nada.

Huis y huis, dando al pueblo,

mientras bebéis la distancia,

motivos para mataros

por las corridas espaldas.

Solos se quedan los hombres

al calor de las batallas,

y vosotros, lejos de ellas,

queréis ocultar la infamia,

pero el color de cobardes

no se os irá de la cara.

Ocupad los tristes puestos

de la triste telaraña.

Sustituid a la escoba,

y barred con vuestras nalgas

la mierda que vais dejando

donde colocáis la planta.

Viento del Pueblo, 1937

Miguel Hernández

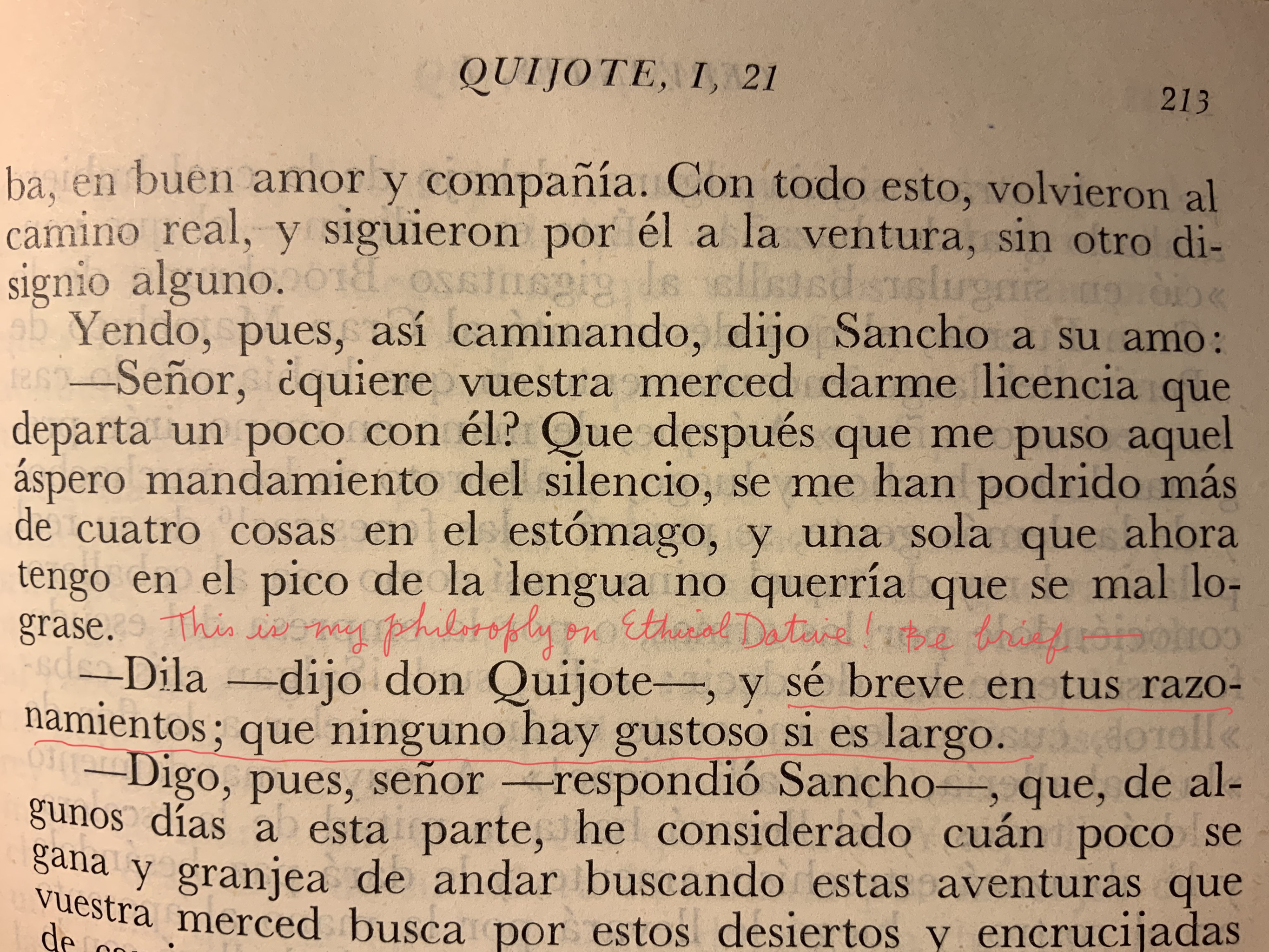

(c) 2021 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Fanfare for the Arch and Monarchic Empyrean

For fanfaronnish, pharaonic, peerlessly peeraged personnages kitted, kilted, severely coiffed and balconic in presence, shod and booted in besotted opulence, blackamoorian brooched, got up in splendid headgear, lorded lads and ladied dames garbed in emblazoned berobement, none…

For sherlockian, sherwoodian, agathonian, haddlepudlian, level-uppity, ‘ello gaffer, day at the races, should I make a cheeky bet, dear olde — you know — not to make a fuss about but, end of, if-I’m-being-honesty, none…

For acid, Mr. Speaker-ish, his-honourable-gentlemanly annunciatory promulgations, retortive denouncements huffed in receivedly syllabic oratory bespoken to bewigged and vested Etonians lounged and draped and clubbed in hoary, leathery chambers and halls amongst antique appurtenances and shafty lighting, none…

For weather reports of “windy everywhere,” none…

… but the English.

(c) 2021 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved