My treatment of Mitchell Glazier’s “The Gazing Ball” (Poetry, May 2025) wasn’t fit for purpose because it came across as testy and dismissive. I’m not equipped nor disposed to be a poetry critic, only a consumer with thoughts. And my thoughts were unruly.

A standard I try to uphold if I’m to sound off is to take a writer seriously. Doing so entails allowing myself to be roiled and provoked by what’s pleased to call itself a poem, having cleared the bar of editors pleased to call themselves poets. It’s not my remit to mock or satirize or deride a text which I find inscrutable.

Approaching a poem confrontationally is to mount resistance to ostensibly impervious utterance. Trying to articulate to myself how or why it gets under my skin implements a working assumption that getting under a consenting reader’s skin is what poetry’s meant to do. It’s easy to lose sight of this premise, because reading aggressively is strenuous and time-consuming. You and I have only the precious moments allotted to us.

Negativity is indifference, not indignation. I have found that sometimes, when I’ve incurred the sunken cost of wrestling with an infuriating text, I’ve begun willynilly to internalize one or more aspects of it, to reach what I call an accommodation, paying it at least a grudging respect.

Just to revisit Glazier’s poem for a moment, I uphold the potential of these utterances to linger in my head, perhaps become memorable:

Absence roughs up / My dead dog in the blood / Of babysitters

Little porcelain / Poppet, hand / The tureen of blood / Now to papa

I’m a gentleman / Dressed in pink paper / Ballooned assless chaps

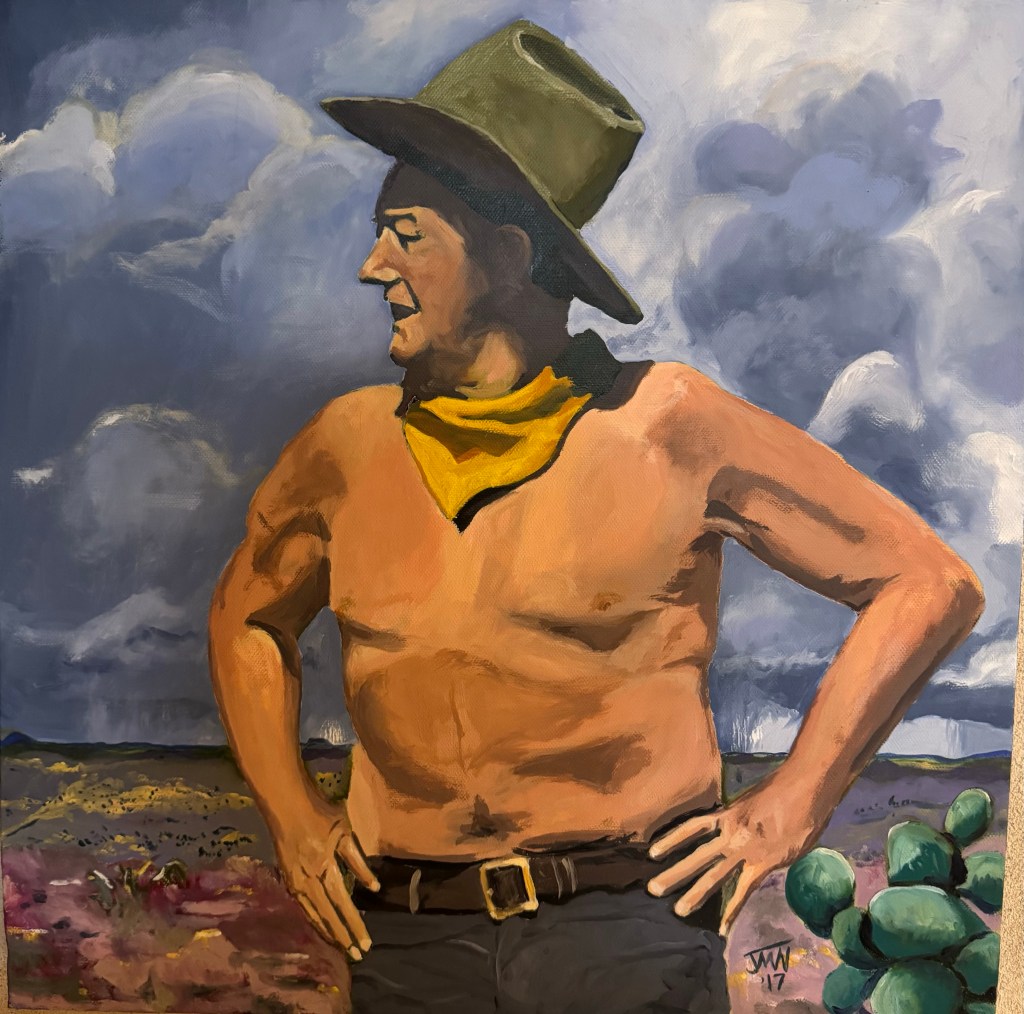

“Assless chaps,” by the way, are an accoutrement of the working cowboy. The following line is “Float the violet quarry,” which I let stand subjunctively on the model of “Cry the beloved country,” exercising reader’s discretion when the text itself isn’t dispositive.

What I have still failed to do is extrapolate a framework in which the elements of “The Gazing Ball” cohere in the service of a unitary message. That may not be an expectation the writer intends to meet or which I’m entitled to have.

I’m stuck with the bias that reading what I call “verse objects” when they’re refractory and I don’t know (or care) if they’re poems or not sharpens my faculty for recognizing, processing and assimilating newness. The only person who need care what I make of the objects is me. Anyone else who does is surpassing kind and someone I want to know.

(c) 2025 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Toyin Ojih Odutola Draws Loud

“Congregation,” 2023, with three figures who seem to be gossiping or complaining, has a camp humor that sometimes pops up in Ojih Odutola’s work. Credit… Toyin Ojih Odutola, via Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; Photo by Dan Bradica Studio. [New York Times caption and illustration]

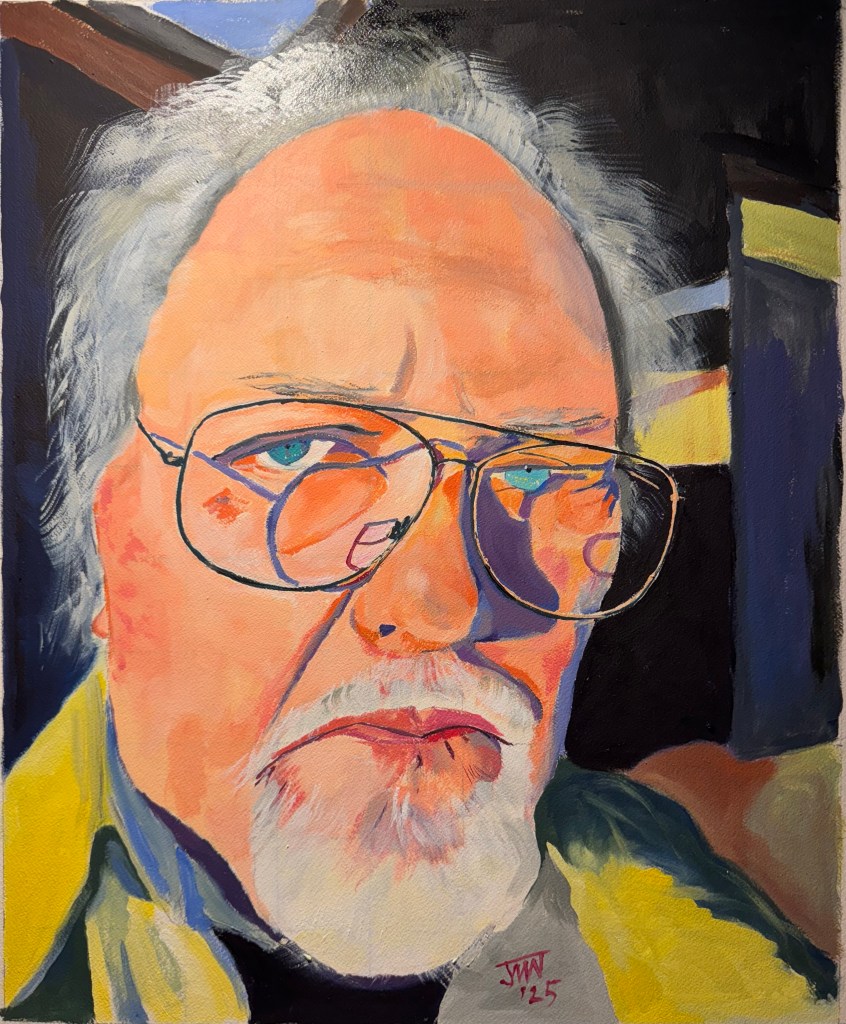

I like how Toyin Ojih Odutola assembles faces from facets, a treatment I strive increasingly, if feebly, to approximate. I describe it to myself in personal shorthand as “envisaging”: implementing visage as a sort of ‘scape rather than anatomical likeness mask. This deep fissure radiating from beside the “nose” is a crevice near the shadow of a promontory, etc. One talks to self, trying to deprogram the brainwashed eye not to “see” what it expects. It exacts a keen and studied form of looking coupled with patient and nuanced handling of media.

Ojih Odutola makes very large drawings — some more than 6 feet high — with charcoal, pastel, graphite and colored pencil. I’d like to know what paper or other surface she uses. The journalist, Siddhartha Mitter, remarks that “her drawings often look like paintings from afar.”

(Siddhartha Mitter, “Toyin Ojih Odutola Is Drawing Up Worlds,” New York Times, 5-22-25)

(c) 2025 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved