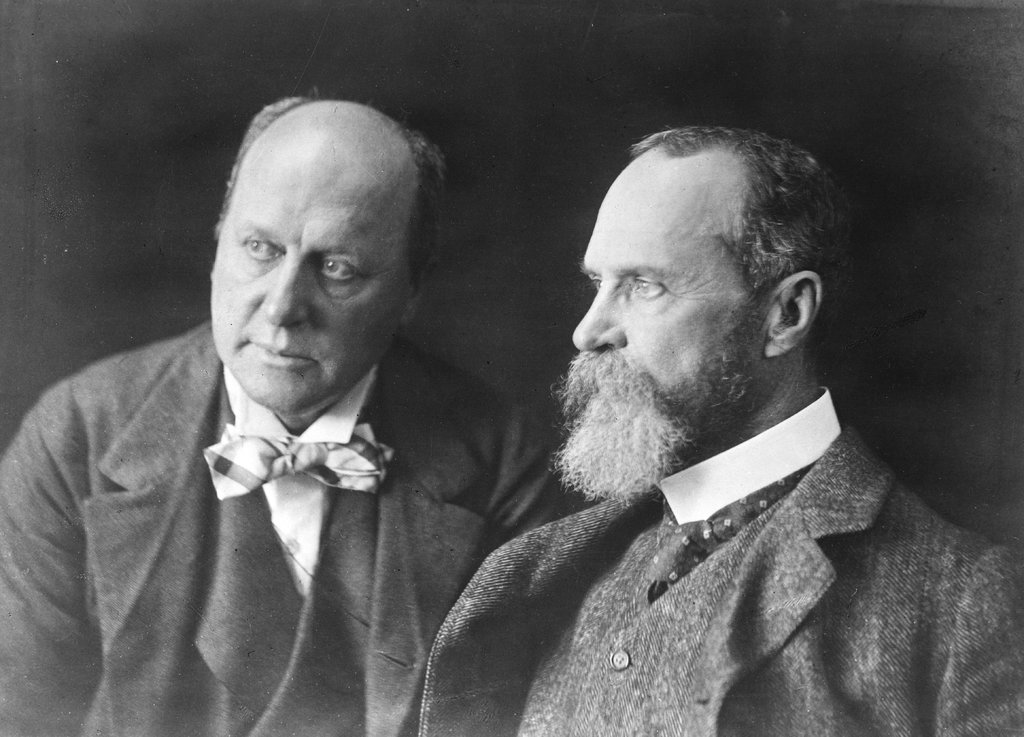

William James arrived penniless in Albany, NY from County Cavan, Ireland in the late 18th century. Over the next 30 years he created a fortune second only to that of the Astor family. His grandsons, novelist Henry and philosopher William, forcefully repudiated their mercantile Irish roots. William wrote to H.G. Wells:

“The moral flabbiness born of the exclusive worship of the bitch-goddess SUCCESS. That — with the squalid cash interpretation put on the word ‘success’ — is our national disease.”

Disavowing their Irishness would not be easy for the brothers, however. Henry crowed that his paternal grandmother, Catherine Barber, was purely English. “She represented… for us in our generation the only English blood — that of both her own parents — flowing in our veins.” He conveniently omitted that John Barber, Catherine’s father, came from Longford County, Ireland.

Henry James remained classist and anti-Irish. William, however, seemed to evolve.

In his Ingersoll Lectures… [William] James scolded his xenophobic audience, insisting that “each of these grotesque and even repulsive aliens is animated by an inner joy of living as hot or hotter than that which you feel beating in your private breast.”

The perception of immigrants as “grotesque and even repulsive aliens” is an ember in America’s private breast that malignant votaries of the bitch-goddess still blow on.

There are at least two types of moral “blindness” — the inability to see the inner lives of individuals unlike ourselves, and also the unwillingness to recognize those aspects of ourselves that quietly underwrite our histories. It is difficult but essential to remember that at one point in the not so distant past we were all trespassers and foreigners.

(John Kaag, “William James’s Varieties of Irish Experience,” NYTimes, 3-16-20)

(c) 2020 JMN

“No Mimetic Ability”

[Stella’s] emphasis on two-dimensional surfaces was a clear rejection of the idea of painting as a window into a three-dimensional space.

A story in one of his mother’s Vogue magazines, featuring models posed in front of a painterly Franz Kline-esque Abstract Expressionist backdrop, provided him with an early clue that art wasn’t only about figuration. At Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., in the early ’50s, when European abstraction was a prevailing force in studio art, Stella was especially influenced by the work of Hans Hofmann, a kind of proto-Abstract Expressionist from the ’40s, and the Bauhaus color theorist Josef Albers. “I had no mimetic ability,” Stella tells me, “but I was never interested in finding one, or cultivating one. No, I worked directly with the materials, actually. The big deal in postwar American painting was ‘its materiality,’ and so that was heaven for me.”

(Megan O’Grady, “The Constellation of Frank Stella,” NYTimes, 3-18-20)

For me as an amateur painter the scariest prospect on the square feet of earth in front of my easel is to grope past mimesis and “work directly with the materials” as Stella puts it. That jump-off hovers just beyond my slogging daubs like the mirage where hot asphalt meets horizon on the highway between Balmorhea and Pecos.

(c) 2020 JMN