I’m intrigued by the tension in Jake Skeet’s [sic] poem: Its title juxtaposes love with death, and its rhythms press against the nettle-like images. The first stanza’s images are scarred and rough with “burr and sage,” “bottles” and the “cirrhosis moon,” yet the lines sound like a nursery rhyme (the first two lines are perfectly trochaic and the third is iambic). Many other lines in this poem are also iambic or trochaic, yet the subject matter is troubled. And the heavy use of monosyllabic words (the entire first line is monosyllabic, as are several others) creates a kind of hammering, unembellished tone.

“Poem: Love Letter to a Dead Body,” Selected by Victoria Chang, NYTimes, 3-24-22.

Victoria Chang’s tight focus leaves room for the reader to negotiate with Jake Skeets’ poem for insight into its thematics. Who can remain in a state of mute contemplation around “scarred” images which monosyllabic trochees and iambs “press against” nursery-rhymishly? Mouthfeel wants substance as well.

on our backs in burr and sage / bottles jangle us awake / cirrhosis moon for eye // fists coughed up / we set ourselves on fire / copy our cousins / did up in black smoke / pillar dark in June // …

“Fists coughed up” unleashes utterance that wanders in a rugged syntactic Badlands where self-immolating voices “copy our cousins / did up in black smoke.” Is “did up” a demotic participle slur for “done up,” meaning “adorned” by black smoke — cremated, massacred, puffed, ritualized? Does the setting afire of self evoke intoxicated exultation or a corybantic ceremony? There may be hints of alcohol decimating a community; jaundiced self-destruction; a canoodling couple nursing a twelve-pack among tossed empties in a forlorn boot hill at town’s edge. In jangled, booze-addled dream, does the desert cough up defiant corpses in a place envisaged as a disrespected ossuary?

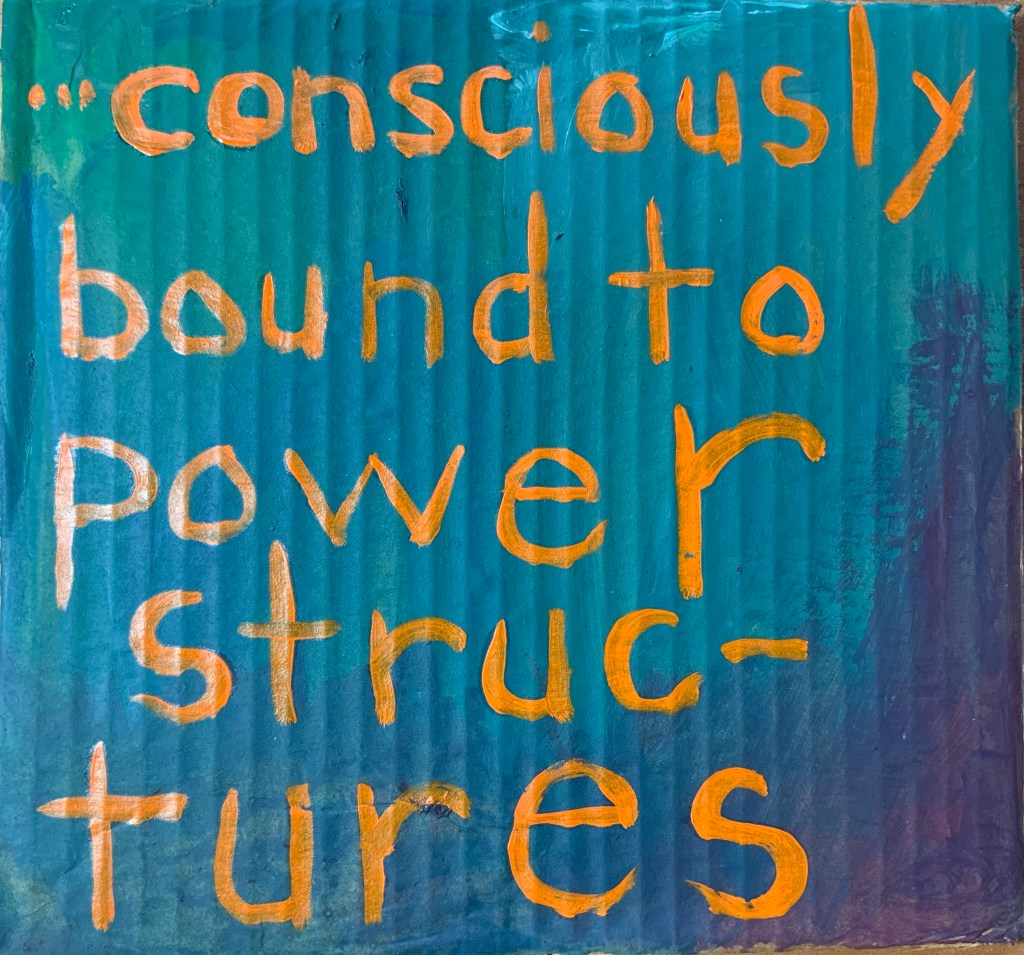

Interpretation feels like a game of why not? A poem’s story space is where words are urged to disgorge a lexical cargo in parsable sequence so as to image forth assertions or perceptions — whether in lean cuts or in extravaganzas. That space can matter to a certain stripe of reader; it’s one the poet-practitioner appears loath to mediate except circumspectly: Skeets’ subject matter is “troubled,”per Chang. Full stop.

Drunktown rakes up the letters in their names / lost to bone / horses graze where their remains are found // and you kiss me to shut me up / my breath bruise dark in the deep // leaves replace themselves with meadowlarks / cockshut in larkspur // ghosts rattle bottle dark and white eyed / horses still hungry / there in the weeds

Beside what could be vexed tribute paid to relations wasted and laid waste, there is twilight among flowers — “cockshut in larkspur” is a lilting embellishment; and there is a sere, haunted “deep” with shapeshifting, avian leaves where horses snuffle in the goathead and sparse grasses.

Little closure otherwise; rather a sense of being ghosted by words, of grasping at shades conjured by the speaker’s kissed breath. Their evasiveness troubles me. Perhaps it’s trouble the poem wishes to cause. The image I carry away keenly is that of the famished nags, “still hungry / there in the weeds.”

(c) 2022 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

How Poetry Feels About Itself

Rae Armantrout’s poem “Smidgins” fulfills an imperative of lyric, which is “Don’t be gassy.” Also another imperative, which is “Talk in riddles.”

My crumpled, wrinkled / blurt / of flesh. // “Let’s face it,” / it says. * …

Ravaged matter expressed as living tissue — flesh — incarnates an impromptu utterance triggered by strong affect expressed as sound — a blurt — in order to urge its startled reflection, glimpsed in a shiny surface, to put a brave face on decline.

Poetry hates itself / the way a child / pretends to fall / and looks around / to see who notices. // As much as any / single smidgin / wants to disappear. * …

The pratfalls a child stages in order to be fussed over and soothed constitute a form of “self-hatred” comparable to that of poetry’s, which confects naughty “accidents” such as talking tissue and bashful smidgins to seek attention and validation while fulfilling its writ to fabricate outré parallels.

Poetry loves itself / the way a baby / loves pleasure, / shadows tickling / its skin. / As a swallowtail, / like a folded note, / sways / on a long / blossom.

A crib-bound infant’s undifferentiated sensory delight in the play on skin of sunlight slicing through the blinds of a darkened room is a form of self-love comparable to how poetry swoons over its own rapture at comparing a splay-tailed kite with a swooshy name at rest on a sweet phrase to what could well be a billet-doux.

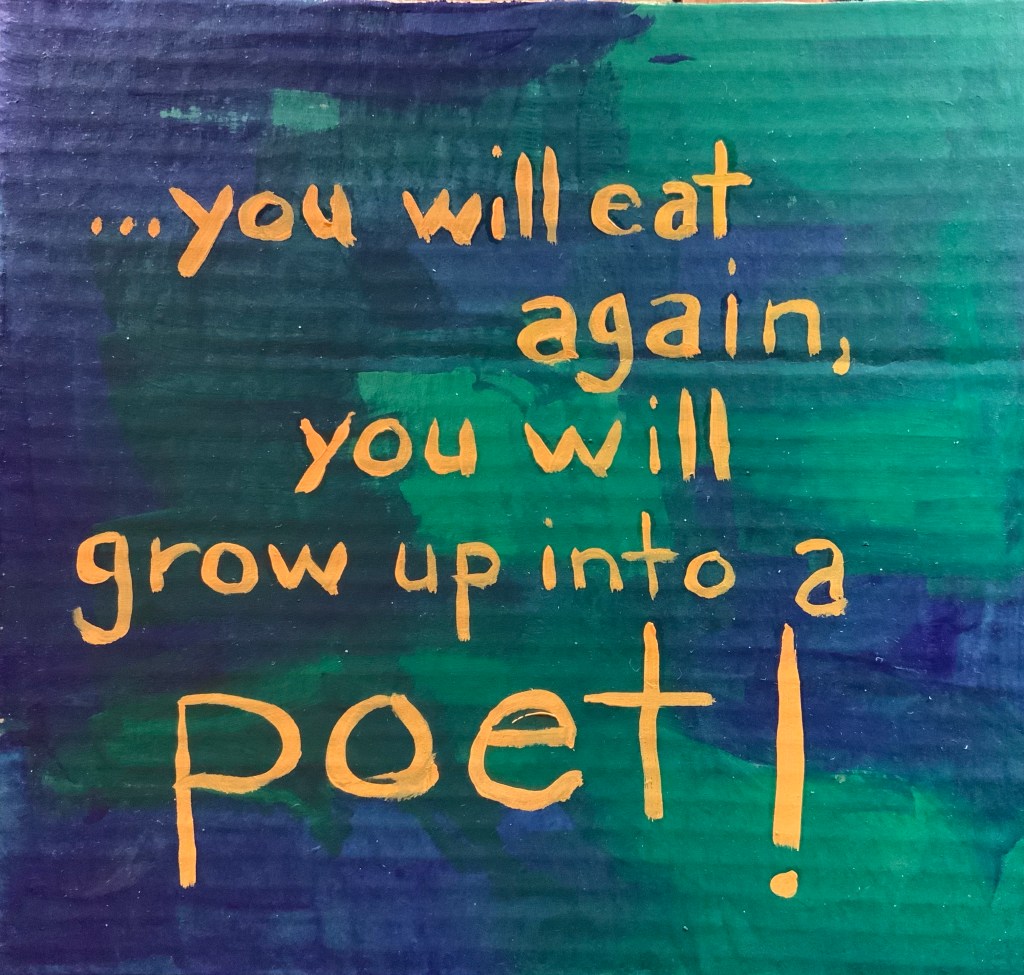

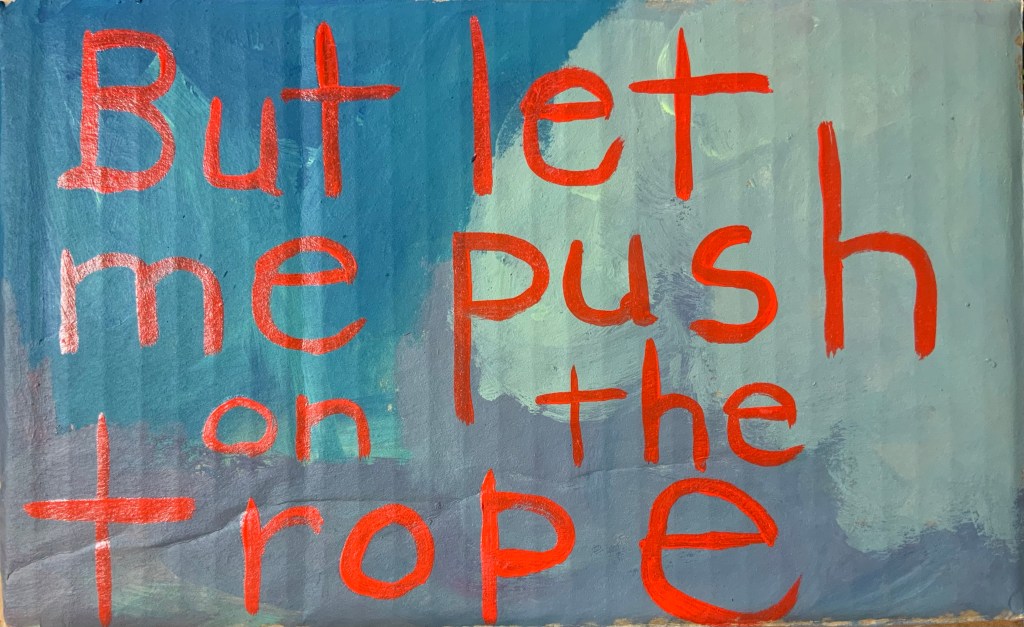

Poetry dines on tropes. Make something voiceless talk. Or take an abstraction, endow it with sentience, and declare it to have feelings about itself that are radically opposed. The only way to seek buy-in for such gambits is hair of the dog, i.e., more cowbell, more daring associative swoops.

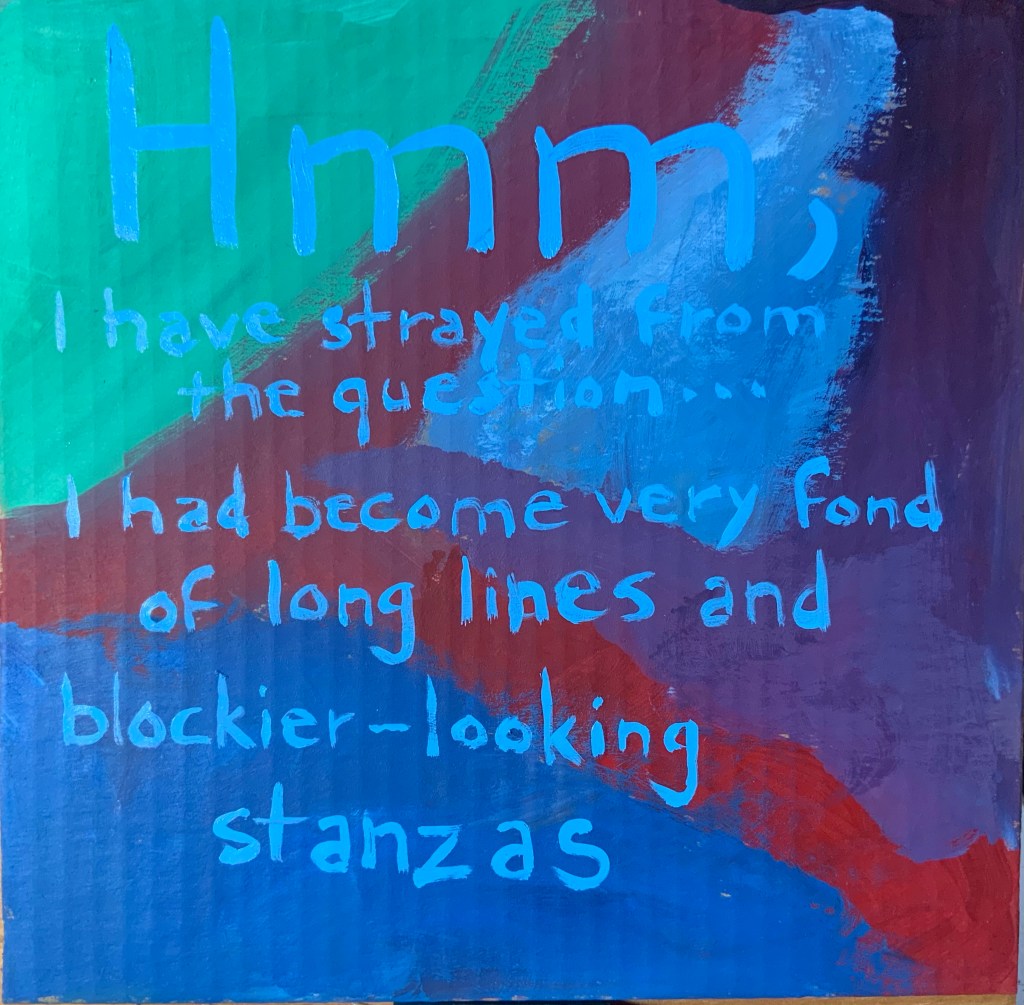

If Armantrout’s lyric succeeds, its oblique shenanigans speak louder than my fussy extrapolations. I don’t say it’s true, but I’m finding that to engage with a poem entails taking possession of it; once handed off by the poet, the poem belongs to me and whoever else wants it. The reading of it is our affair, and includes license to talk back to the poem, to get in its face.

(Rae Armantrout, “Smidgins,” newyorker.com, 3-28-22. The entire poem is quoted.)

(c) 2022 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved