Nabokov and Borges differed over how translation should be done, the former favoring literalness (“The clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase”), the latter transformation (“Translation is… a more advanced stage of writing”). I gravitate increasingly towards Nabokov’s view, driven most by my practice in reading Arabic.

I like the Spanish word “fidedigno” for its suggestion of “faith-worthiness.” A faith-worthy translation isn’t gassy with interpretation; pays all but servile deference to the letter of the original; doesn’t reach unduly for the “spirit” of the text — that’s for the separate realm of commentary. Equally important, the faith-worthy translation resists overprocessing the source into target-friendly modalities, presuming that the reader must always be protected from strange-sounding language.

I’m on verse 5:60 of the Quran:

قُلْ هَلْ أُنَبِّئُكُم بِشَرٍّۢ مِّن ذَٰلِكَ مَثُوبَةً عِندَ ٱللَّهِ ۚ مَن لَّعَنَهُ ٱللَّهُ وَغَضِبَ عَلَيْهِ وَجَعَلَ مِنْهُمُ ٱلْقِرَدَةَ وَٱلْخَنَازِيرَ وَعَبَدَ ٱلطَّـٰغُوتَ ۚ أُو۟لَـٰٓئِكَ شَرٌّۭ مَّكَانًۭا وَأَضَلُّ عَن سَوَآءِ ٱلسَّبِيلِ ٦٠

My reading is this:

“Say: Do I inform you of worse than that, requital-wise, chez God? The one whom God cursed him and He was angry with him and made of them [plural pronoun!] monkeys and pigs and he worshiped idols. Those are worse, place-wise, and more astray from the sameness of the way.”

My reading is a trot, not a translation. It tries to peg analytically the operation of elements in the source text. I try to seize on what seems a core meaning of a word in a Wehr listing; this can mean passing over a dandy English phrase standardized by usage (ex. “right path” versus “sameness of the way”).

About those monkeys: In English a “simian” is an ape or a monkey, but an ape isn’t a monkey. I don’t find the distinction between the two as clearly marked in Arabic and Spanish. (Spanish doesn’t have different words for “elk” and “moose,” either.) For qird (its plural qiradaẗ occurs in the verse), Wehr lists “ape” and “monkey.” Lane lists “ape,” “monkey” and “baboon.”

I’ll cite two versions of the verse to show what solutions translators can hit upon.

Shall I tell thee of a worse (case) than theirs for retribution with Allah? (Worse is the case of him) whom Allah hath cursed, him on whom His wrath hath fallen and of whose sort Allah hath turned some to apes and swine, and who serveth idols. Such are in worse plight and further astray from the plain road.

— M. Pickthall

Di: <<No sé si informaros de algo peor aún que eso respecto a una retribución junto a Dios. Los que Dios ha maldecido, los que han incurrido en Su ira, los* [Cortés’s note: ‘Los judíos. C2:65’] que Él ha convertido en monos y cerdos, los que han servido a los taguts, ésos son los que se encuentran en la situación peor y los más extraviados del camino recto.>>

(Say: “I don’t know whether to inform you of something worse than that respecting a retribution next to God. Those whom God has cursed, those who have incurred His wrath, those* [Cortés’s note: ‘The Jews. Quran 2:65’] whom He has converted into monkeys and pigs, those who have served the idols, they are the ones who find themselves in the worst situation and strayed furthest from the straight road.”)

— Julio Cortés

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

Where Dems Fell Foul of the Electorate, On Charcoal, and Living in the Moment

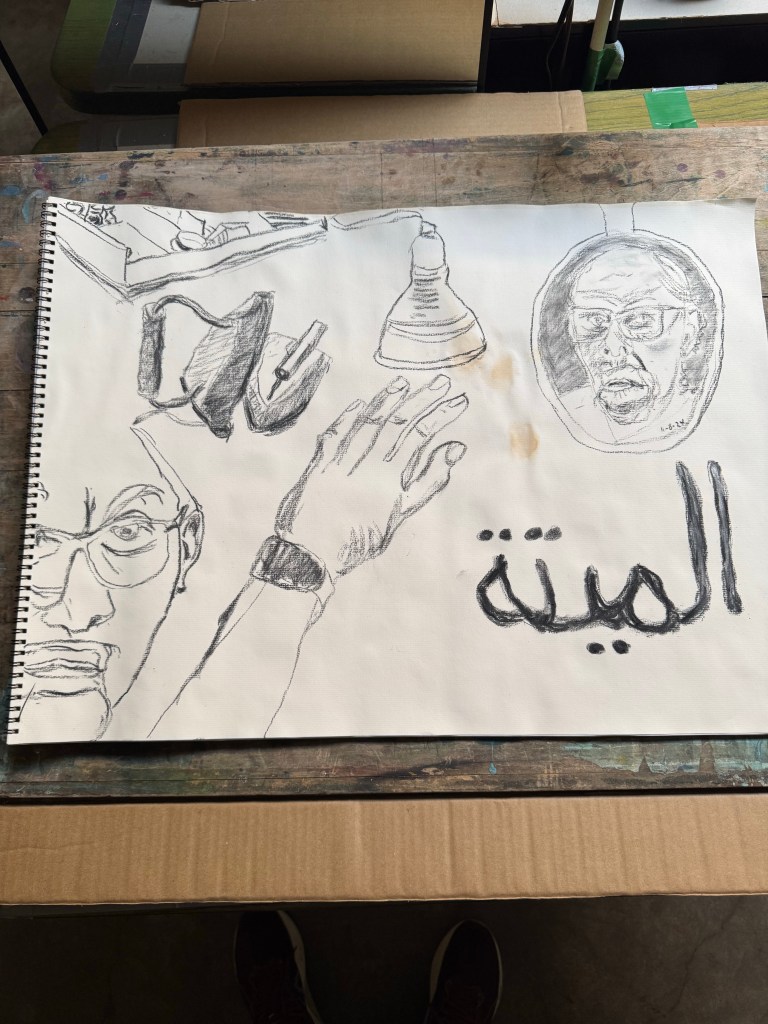

“Instead of focusing on the voters they were losing, Biden and the Democrats kept focusing on the voters they were winning.” Ezra Klein’s comment reinforces my sense that I should continue trying to draw with willow charcoal. It’s for me an uncongenial medium and I’m not winning it over to my side, which argues for continuing the struggle. Stay the course, says my bitter angel. I call my ham-fisted sketch “Page Killer,” a bit of jargon resurrected from my newspaper advertising days. A page killer was an ad big enough to crowd any other ad off the page. Room was left for a smidgin of editorial matter. An advertiser could spend less than the cost of a full page and still get the benefit of having no competition for eyeballs. An ad spanning two full pages was called a “double truck.” Merchants pestered us to guarantee placement of their ad on a lefthand page in section A, but we salespeople were tasked with holding the line, our mantra being, “We do NOT sell position!” Our newspaper had the greatest penetration of any in the region, which gave us leverage. My department, Display Advertising, was its beating heart. The ads were the content; the news was just filler.

Now and then I let the me called self remain unsure of something when I know full well I could resolve doubt with a peek at the internet known today as “research.” There’s something delicious in giving the mind rein to rusticate in all manner of sweet conjecture, or simply to set the matter aside as not worth pursuing. Will learning how the Stutz-Bearcat got its name improve my life?

Frank Bruni’s feature “For the Love of Sentences” has a quotation which suggests that the suspension of certainty could look a lot like what’s now called “living in the moment.” Isn’t that supposed to be a good thing?

“I belong to the last generation of Americans who grew up without the internet in our pocket. We went online, but also, miraculously, we went offline… We got lost a lot. We were frequently bored. Factual disputes could not be resolved by consulting Wikipedia on our phones; people remained wrong for hours, even days. But our lives also had a certain specificity. Stoned on a city bus, stumbling through a forest, swaying in a crowded punk club, we were never anywhere other than where we were.” ([Quote submitted by] Janice Aubrey, Brooklyn, N.Y.)

(c) 2024 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved