Below is jargon improvised for gauging how a translation navigates its source text. Note how the verbiage is strewn with hedging adverbials, conceding a priori that the labels are judgments, which by definition are subjective, privative, compromised, blinkered and fallible. (See “U.S. Supreme Court.”)

Congruent: matches the source text fairly closely, with minimal liberties taken for readability.

Omissive: suppresses elements of the source text without obvious justification.

Expansive: adds interpretive structure or content not discernible in the source text but plausibly deriving from it.

Inventive: carries the “expansive” element to a level not obviously supported by the source text.

Transgressive: departs from the source text in a way that arguably betrays the poem’s letter or spirit.

Omissive was added late. It’s a watchword for the position that loss must entail gain; if the translation discards a feature of the source text which the target language is capable of emulating, a benefit should be realized from the curtailment. If gain is perceptible, the translation accrues congruency; if not, it steers a tick in the remiss direction.

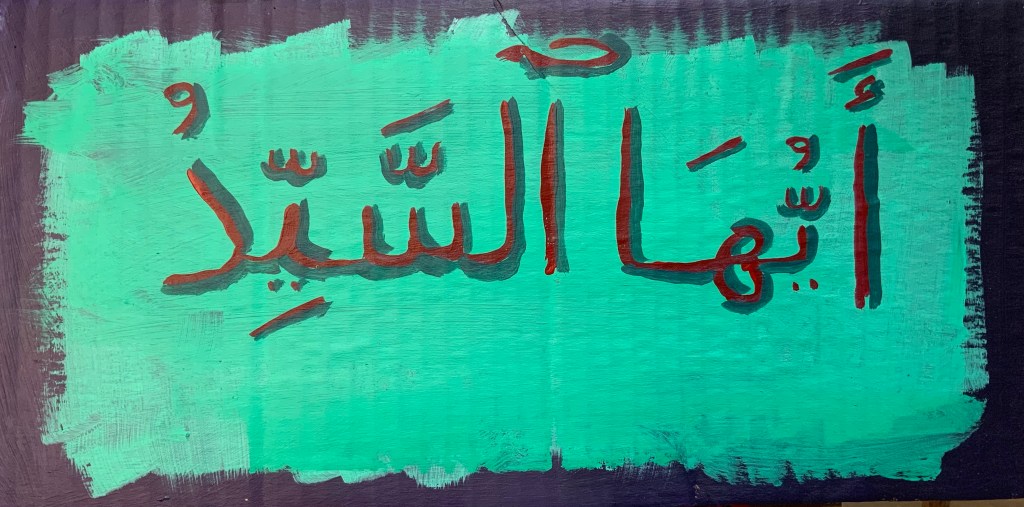

The first line of the section of Gilgamesh’s Snake titled “The Lost Beginning” by Gareeb Iskander (1) attracts attention. It’s a vocative construct.

O master!

‘ayyuhā-s-sayyidu

Master! (2)

The vocative is a Hey, you, listen up! utterance involving a particle — ‘O’ in English, ‘ayyuhā in Arabic — followed by a noun or pronoun — here, sayyidun, master, sir, lord, chief. (3) Iskander leaves out the particle in its translation, perhaps from a desire not to sound mannered or highflown. However, sayyidun connotes prestige. It comports well with prefacing by “O.” The formal tone isn’t amiss contextually, and the source text is respected. Iskander’s translation could be tagged Omissive.

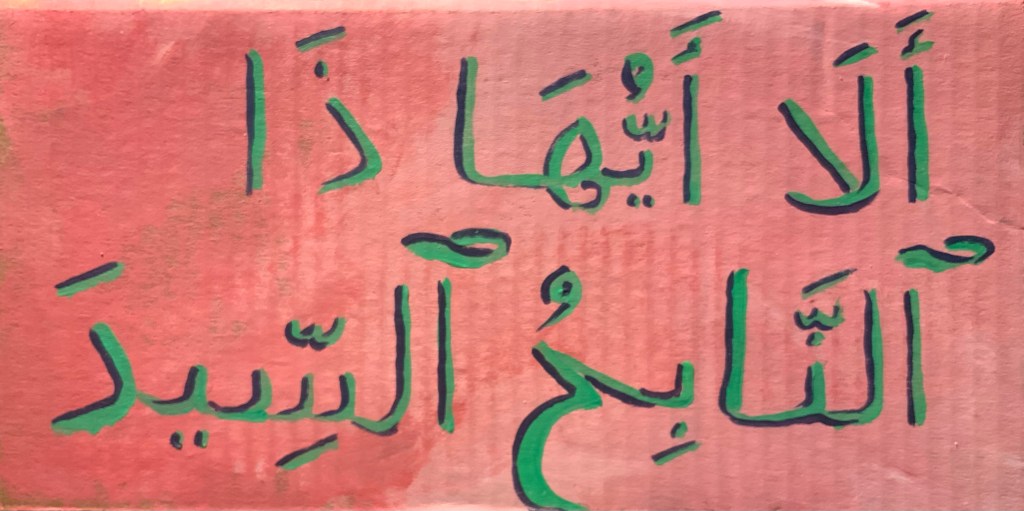

Here’s a smattering of Wright’s exposition on the vocative (4):

“‘ayyuhā and yā ‘ayyuhā… require after them a noun, singular, dual or plural, defined by the article, and in the nominative case… The demonstrative ḏā is also admissible….”

Wright illustrates the construction with Arabic phrases translated into fragrant period English. Here are three of them: Thou there, come forward!; O thou there, whose soul passion (or grief) is killing; O thou there, who barkest at (revilest) the Bènū ‘s Sīd.

Notes

(1) Gilgamesh’s Snake and Other Poems, Ghareeb Iskander, Bilingual Edition, Translated from the Arabic by John Glenday and Ghareeb Iskander, Syracuse University Press, 2015.

(2) The published translation (“Iskander”) is in italics beneath my rendering and transliteration using this jury-rigged character set: ‘ a ā A i ī u ū ay aw b t ẗ ṯ j ḥ ẖ d ḏ r z s š ṣ ḍ ṭ ẓ ^ ḡ f q k l m n h w y.

(3) Hans Wehr, A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, Edited by J. Milton Cowan, Cornell University Press, 1966.

(4) W. Wright, A Grammar of the Arabic Language, Simon Wallenberg Press, 2007. Reprint of the classic work first published in 1874, and updated in 1896.

(c) 2022 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

The Case for Rhythm and Emptiness

Brazilian artist Maxwell Alexandre speaks of how exposure to Kerry James Marshall’s painting made him aware of “an absence of representation. You would ask a Black kid to draw a person and he would draw a white person… Just by looking at [Marshall’s] body of work, where every character is Black, it shattered something.”

It’s intriguing to speculate what form children’s drawn depictions of persons of different race would take.

This well-spoken painter’s kitchen-sink approach to media is beguiling. His figures, brushy and flat, jump off their kraft paper with something of a fashion flair. A barefoot, disquietingly faceless male in dangling bib overalls sports a septum ring and assorted bling, along with blonde hair, as his sole discernible features.

Alexandre identifies with the “Black figuration” movement in Brazilian painting. It fills a vital gap, he says.

“… You are much likelier to be successful if you deal with this [movement] than if you want to discuss rhythm and emptiness. But you flatten the possibility of expression for young Black artists. You don’t have white figuration. Because white people have been representing the white figure for so long, they can move on to the sublime.”

“Move on to the sublime”! The lofty phrase sticks a landing. Regarding the direction his own work may take, Alexandre speculates: “It becomes abstract, which I would like to do more of.”

As would I. The way he paints his becoming mindset with words, not just shoe polish, Alexandre incites me to think of abstraction as the endpoint, a destination hard to reach, but out there.

(Arthur Lubow, “How Rollerblading Propelled Maxwell Alexandre’s Art Career,” New York Times, 10-25-22)

(c) 2022 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved