Consulting an Arabic dictionary involves looking up a word’s “root,” usually comprising three consonants. Words formed from the root are listed, with their translations, along with idioms in which the word occurs. What the root is may not be apparent on first blush, so lookup can entail a check of competing options. The roving linguist may glimpse, in passing, terminology that induces reflection. I wasn’t seeking it, for example, but I found [faDDa bakāra(t)a-hā], to deflower a girl.

The verb [faDDa] means to break or force open. The dictionary calls [bakāra(t)] virginity; other sources list maidenhead and hymen. As I see it, the phrase could be read as “to break the hymen.” The literal Arabic is plainspoken, at least, whereas the florid tropes of “deflowering” and “virginity” affixed to the phrase in Western culture (French défloration, Spanish desvirgar, etc.) are synonymous with despoilment — the sullying of purity. Compare it to the cliché in which a mature woman who initiates a bashful young male may be credited with “making a man of him.”

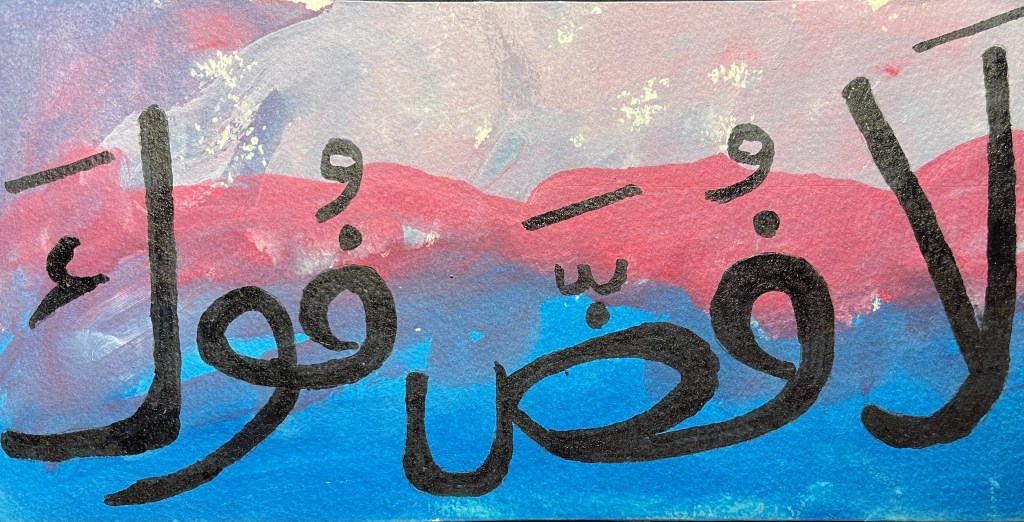

On the other hand, there are pleasant surprises such as [lā fuDDa fūka], how well you have spoken!

It’s a passive use of [faDDa] which, depending on your choice of variant, might be translated literally: “your mouth [muzzle, orifice, aperture, hole, vent, embouchure, mouthpiece…] was not broken open [pried, forced, undone, snapped, scattered, dispersed, perforated, pierced…]. If pressed to provide a tonal equivalent for it, I might venture a Texan idiom such as “You ain’t just a-woofin’.” It would take a feel for Arabic which I don’t possess to know whether it struck the right note.

(c) 2022 JMN — EthicalDative. All rights reserved

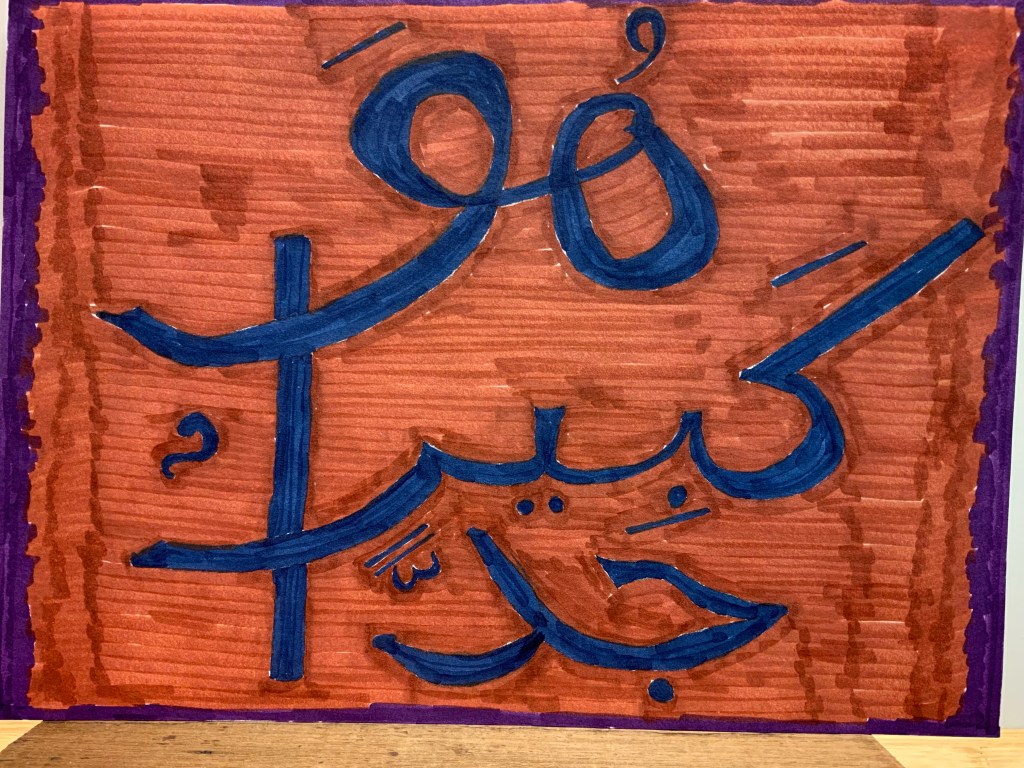

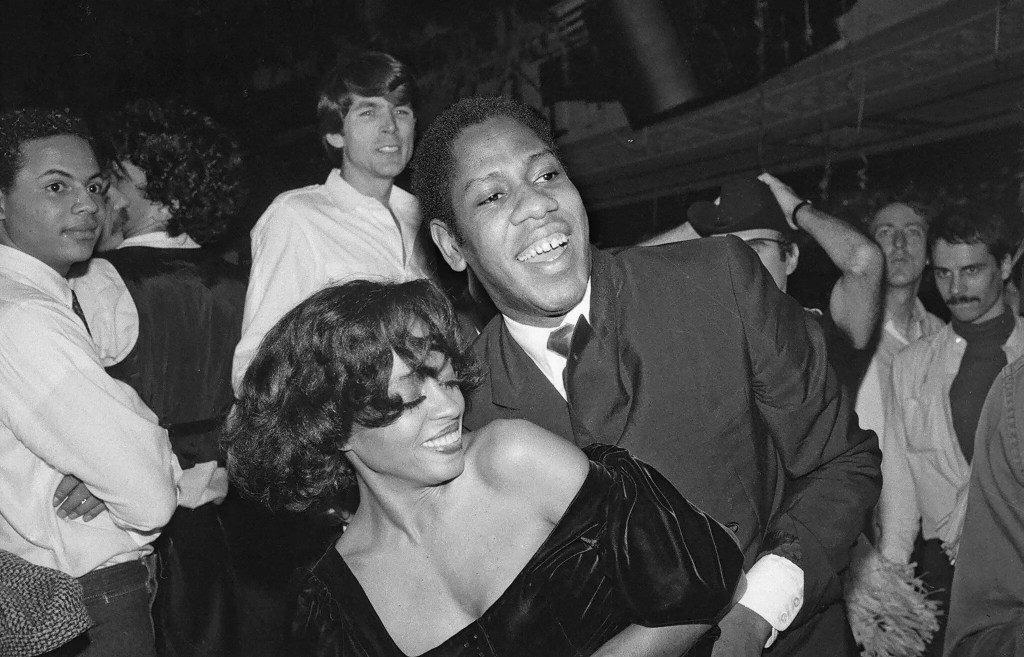

‘That Damned Mania to Write’

This gallery contains 1 photo.

Once upon a time (Érase una vez…, they say in Spanish), I couldn’t conceive of settling for less than being a published poet. I was too callow and unstable, however, to give the project sustained hard work. I’m content now … Continue reading →